You made about 35,000 decisions today. What to wear. What to eat. Whether to hit snooze. Whether to reply to that text now or later.

Most of those decisions felt automatic. Easy. Like you were in control the whole time.

You weren’t. Your brain was running on autopilot. And that autopilot has some serious bugs.

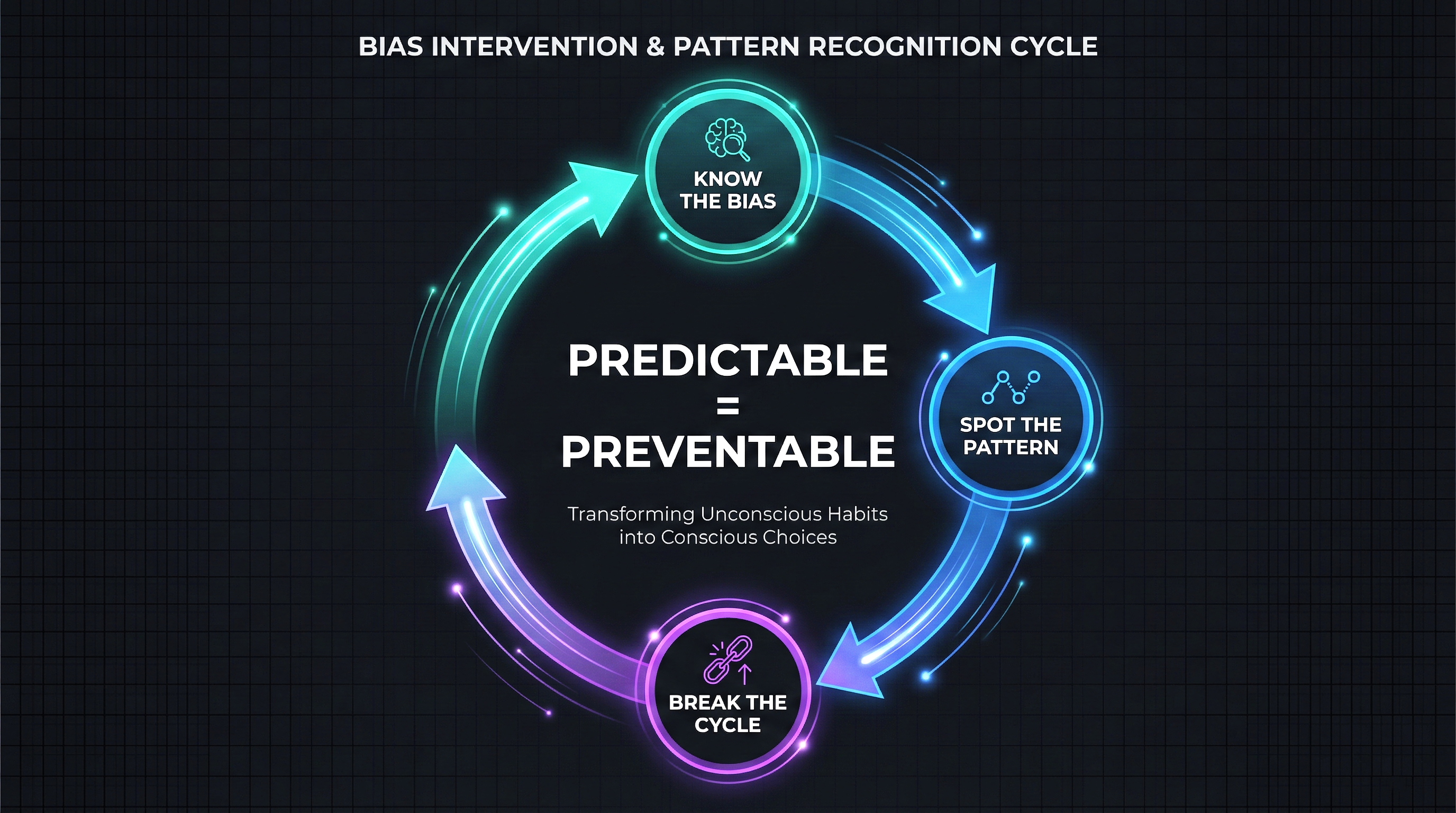

Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky spent decades mapping these bugs. They called them heuristics and biases. Mental shortcuts that help you think fast but often lead you somewhere you didn’t mean to go. As behavioral economist Dan Ariely puts it, we aren’t just irrational. We’re predictably irrational. The same mistakes show up again and again, in the same patterns, across millions of people.

Here are seven of the worst offenders. And what you can do about them.

Your Brain’s Shortcuts Have a Dark Side

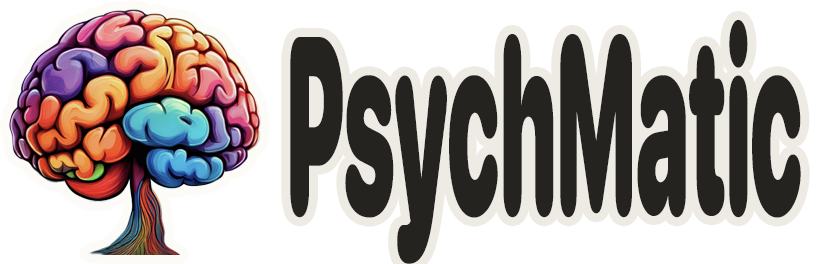

Your brain processes roughly 11 million bits of information per second. But your conscious mind can only handle about 50. That’s a massive gap. To bridge it, your brain relies on heuristics. These are mental rules of thumb that let you make snap decisions without analyzing every detail.

Most of the time, they work fine. David McRaney, author of You Are Not So Smart, explains it this way: heuristics speed up processing in the brain, but sometimes make you think so fast you miss what’s important.

Here’s the problem. These shortcuts were built for a world of saber-toothed tigers and berry picking. Not mortgage rates and retirement planning.

When Shortcuts Become Traps

Your brain’s fast-thinking system kicks in automatically. It’s intuitive, emotional, and instant. The slow-thinking system is rational, logical, and deliberate. But it takes effort. And your brain is lazy. It avoids effort whenever possible.

Robert Cialdini’s research on decision-making shows what happens when people are tired, rushed, or overloaded. They stop thinking carefully and fall back on a single shortcut. Persuasion experts know this, which is why the hidden rules of persuasion are built around catching you at your weakest. In one study, people under time pressure chose a camera with eight “superior” features over one with only three. But the three features were the ones that actually mattered. Quality of lens, mechanism, and pictures. The eight features included things like “comes with a shoulder strap.”

“We are pawns in a game whose forces we largely fail to comprehend. We usually think of ourselves as sitting in the driver’s seat, with ultimate control over the decisions we make. But, alas, this perception has more to do with our desires than with reality.” - Dan Ariely

When you’re tired, stressed, or in a hurry, your brain doesn’t get smarter. It gets lazier. And that’s exactly when biases hit hardest.

Recommended read: Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely. A fascinating look at the hidden forces behind our everyday irrational choices.

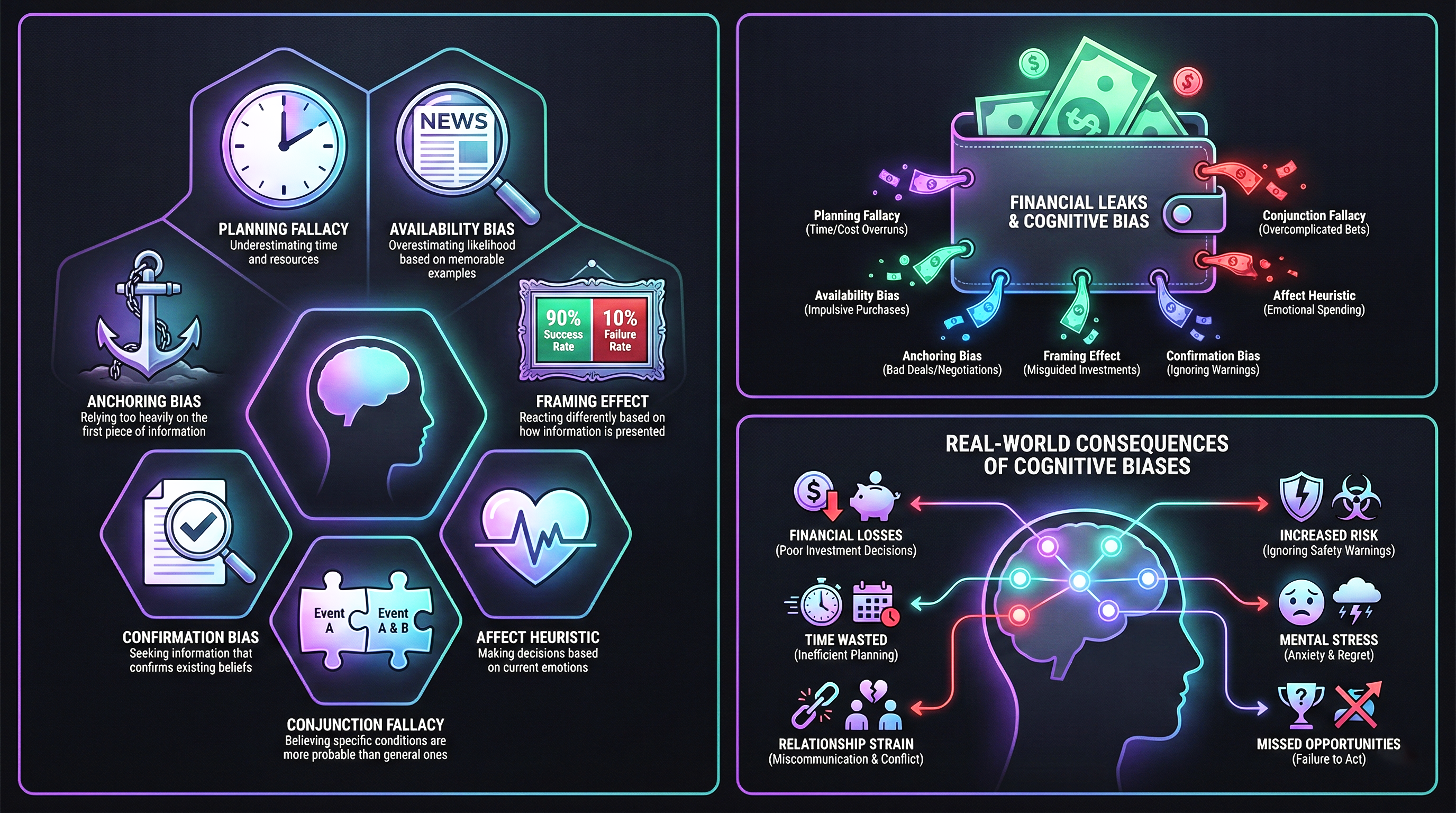

The 7 Biases You Need to Know

Let’s break down the seven cognitive biases that do the most damage in your daily life. You’ll recognize yourself in every single one.

1. The Planning Fallacy

Every morning, you make a to-do list. How often do you actually finish it? If you’re like most people, maybe once a month.

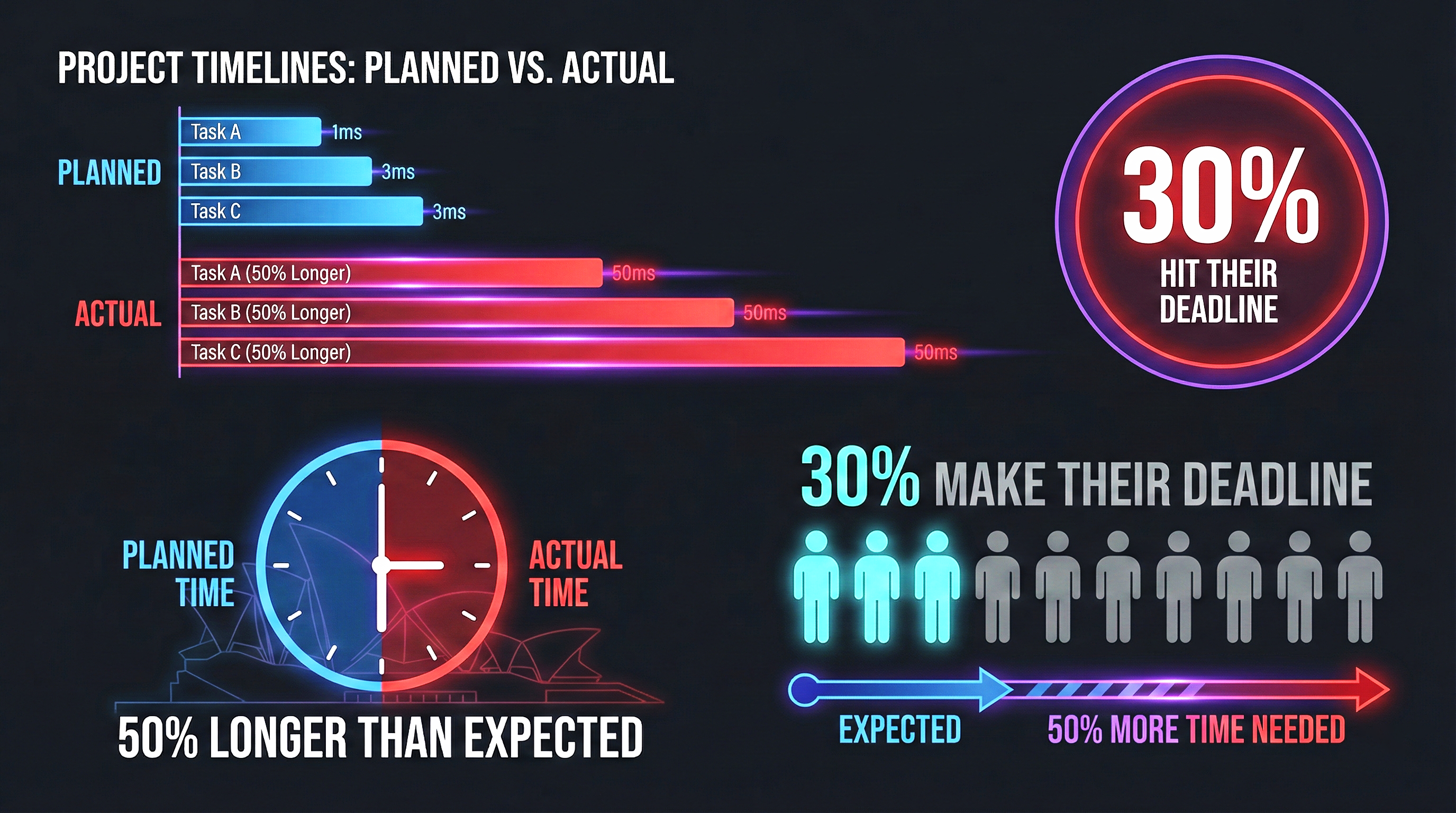

Rolf Dobelli calls this the planning fallacy. You systematically take on too much. And the wild part? You’ve been making to-do lists for years. You know you overestimate what you can do. But you keep doing it anyway.

Canadian psychologist Roger Buehler tested this with university students. He asked them to predict when they’d finish their theses. He wanted two dates. A “realistic” one and a “worst-case scenario” one. The results were brutal:

- Only 30% hit their realistic deadline

- On average, students needed 50% more time than planned

- They blew past even their worst-case estimate by a full seven days

The planning fallacy gets worse in groups. The Sydney Opera House was supposed to cost $7 million and open in 1963. It finally opened in 1973 at a cost of $102 million. That’s fourteen times the original budget.

2. The Availability Heuristic

Quick. Are there more words in English that start with the letter K, or more words that have K as the third letter?

Most people say K-starting words. The real answer? Words with K in the third position outnumber them by roughly three to one. But words starting with K come to mind faster. So your brain assumes they’re more common.

This is the availability heuristic. You judge how likely something is based on how easily examples come to mind. Plane crashes feel common because they make the news. Asthma deaths feel rare because they don’t. But asthma kills far more people.

As Charlie Munger once warned: “An idea or a fact is not worth more merely because it is easily available to you.”

3. The Anchoring Effect

Kahneman and Tversky gave high school students five seconds to estimate this:

8 x 7 x 6 x 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1

The median answer? 2,250. A different group estimated:

1 x 2 x 3 x 4 x 5 x 6 x 7 x 8

Their median answer? 512. Same problem. Same answer (40,320). But the starting number dragged everyone’s guess in its direction.

The anchoring effect gets even stranger. In another experiment, subjects spun a random wheel numbered 0 to 100. Then they were asked to guess the percentage of African countries in the United Nations. People who spun a higher number gave higher estimates. A completely random wheel changed their answer to a factual question.

4. The Framing Effect

Imagine a disease will kill 600 people. You have two options:

- Option A: Saves 200 lives

- Option B: 33% chance all 600 survive, 66% chance nobody survives

Most people pick A. Safe choice. Now look at the same options framed differently:

- Option A: 400 people die

- Option B: 33% chance nobody dies, 66% chance all 600 die

Suddenly most people pick B. The math is identical. But the word “die” makes you gamble to avoid the loss.

This is the framing effect. The way information is presented completely changes your decision. Meat labeled “99% fat free” seems healthier than meat labeled “1% fat.” They’re the same product. Your brain doesn’t care.

5. Confirmation Bias

You don’t search for the truth. You search for evidence that you’re already right.

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek out, remember, and favor information that supports what you already believe. McRaney points out that the contents of your bookshelf and your browser bookmarks are a direct result of it. You surround yourself with ideas that feel familiar and comfortable.

This bias is invisible. You genuinely believe you’re being objective. That’s what makes it so dangerous. It’s also one of the main reasons smart people fall for fake news. The stories that confirm your worldview slip right past your defenses.

6. The Affect Heuristic

You meet someone new. Within seconds, you’ve sorted them into one of two buckets: good or bad. That snap judgment then colors everything you learn about them afterward.

The affect heuristic is your brain’s habit of making decisions based on gut feelings rather than careful analysis. First impressions stick. Research by Wilielman, Zajonc, and Schwartz showed that people who saw a happy face flash briefly on a screen before seeing an unfamiliar symbol liked that symbol more. And when the same symbol appeared later with a different expression, they didn’t change their answer.

Your first impression becomes your anchor. Then you make everything else fit around it.

7. The Conjunction Fallacy

Here’s one that trips up even experts. Read this scenario:

“Seattle airport is closed. Flights are canceled.”

Now read this one:

“Seattle airport is closed due to bad weather. Flights are canceled.”

Which is more likely? Most people pick the second. But the first is always more likely. Adding “due to bad weather” makes the story more specific, which means it can only be true in fewer situations. A bomb threat, an accident, or a strike could also close the airport.

Rolf Dobelli explains that the conjunction fallacy happens because your intuitive brain loves plausible stories. The more detailed a scenario sounds, the more real it feels. Even though the math says otherwise.

“Two types of thinking exist. The first kind is intuitive, automatic, and direct. The second is conscious, rational, slow, laborious, and logical. Unfortunately, intuitive thinking draws conclusions long before the conscious mind does.” - Rolf Dobelli

Recommended read: The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli. 99 short chapters on the most common thinking errors and how to avoid them.

How These Biases Cost You Real Money and Time

These aren’t just interesting psychology factoids. They drain your bank account, wreck your schedule, and steer your relationships in ways you don’t notice.

| Bias | Real-World Cost | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Planning Fallacy | Blown budgets and deadlines | Home renovations cost 2-3x the estimate |

| Availability Heuristic | Wrong risk assessment | Buying flight insurance after watching a crash documentary |

| Anchoring Effect | Overpaying for everything | ”Was $200, now $99!” feels like a deal even if it’s worth $60 |

| Framing Effect | Manipulated choices | Choosing “95% effective” treatment over “5% failure rate” |

| Confirmation Bias | Echo chambers and bad investments | Holding a losing stock because you only read bullish news |

| Affect Heuristic | Snap judgments that stick | Hiring the “likable” candidate over the qualified one |

| Conjunction Fallacy | Falling for detailed scams | Elaborate fraud stories feel more believable than vague ones |

The Fatigue Multiplier

Here’s what makes it worse. Every one of these biases hits harder when you’re mentally drained. Websites and apps also exploit these weaknesses through dark patterns that trick your brain into clicking, subscribing, and spending. Cialdini’s research shows that infomercial producers intentionally air ads late at night because tired viewers can’t resist the emotional triggers. Likable hosts, dwindling supplies, enthusiastic audiences. It all works better when your brain is too exhausted to push back.

Sleep researchers have found something even more disturbing. Fully rested artillery teams often challenge orders to fire on civilian targets. After 24 to 36 sleepless hours, they obey without question. If fatigue can override the decision to shell a hospital, imagine what it does to your late-night Amazon cart.

Recommended read: The Undoing Project by Michael Lewis. The gripping story of Kahneman and Tversky’s partnership and how they changed how we think about thinking.

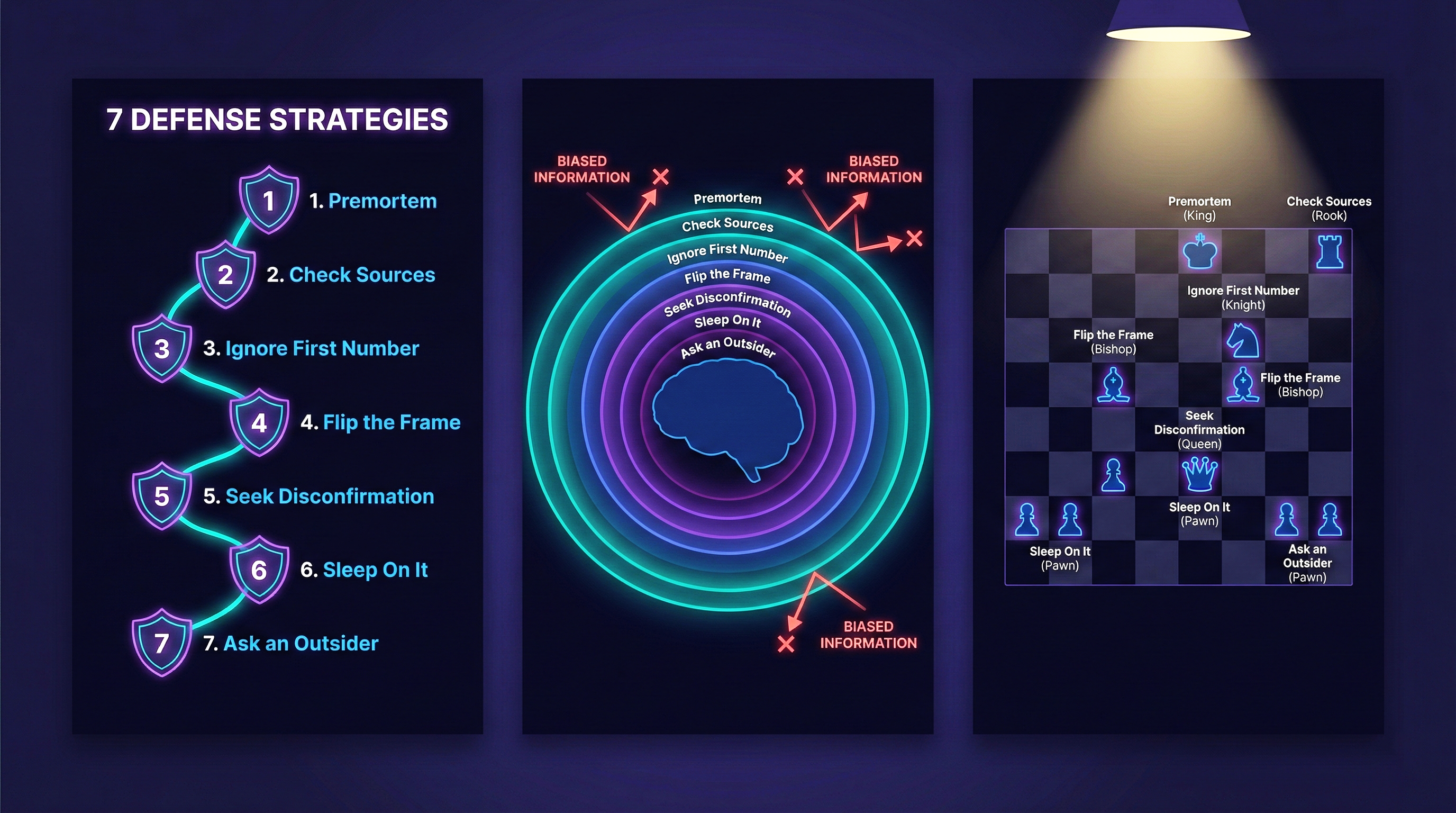

How to Fight Your Own Brain

You can’t delete cognitive biases. They’re built into your neural hardware. But you can learn to spot them and design your environment to reduce their grip.

-

Run a premortem. Before starting any project, imagine it has failed spectacularly. Write down every reason why. This technique, described by psychologist Gary Klein, forces your brain to consider problems it would normally ignore. It directly fights the planning fallacy.

-

Check your sources. When you feel certain about something, ask yourself: Am I certain because of evidence, or because examples come to mind easily? If you can only think of vivid, dramatic examples, the availability heuristic is probably fooling you.

-

Ignore the first number. Whenever you see a price, salary offer, or time estimate, remember that the first number you encounter becomes your anchor. Deliberately generate your own independent estimate before looking at anyone else’s.

-

Flip the frame. When making a decision, restate the options in opposite terms. If something is described as “90% success rate,” rephrase it as “10% failure rate.” If your gut reaction changes, the framing effect was driving your choice.

-

Seek disconfirming evidence. Actively look for information that proves you wrong. Ask someone who disagrees with you to make their case. This is the hardest step because confirmation bias makes opposing views feel threatening. But it’s also the most powerful.

-

Sleep on it. Literally. Never make a major decision when you’re tired, rushed, or emotional. Your slow-thinking system needs energy to override the fast one. Give it that energy.

-

Ask an outsider. Dobelli highlights a simple fix for the planning fallacy: ask someone who isn’t involved in the project to make their own forecast. Outsiders don’t share your blind spots. Their estimates are almost always more accurate.

Recommended read: You Are Not So Smart by David McRaney. A witty, eye-opening tour of 48 ways your brain deceives you daily.

The Bottom Line

Your brain isn’t broken. It’s just running software designed for a different world. The mental shortcuts that kept your ancestors alive on the savanna now trip you up at the grocery store, in the office, and on your phone.

The mistakes are predictable. They show up in the same patterns, in the same situations, across every human being on the planet. That’s actually good news. Because if the errors are predictable, they’re also preventable.

You won’t catch every bias every time. Nobody does. But the simple act of knowing they exist changes the game. As Don Redelmeier, one of Kahneman and Tversky’s most devoted students, put it after reading their work for the first time: “What was so compelling is that the mistakes were predictable and systematic. They seemed ingrained in human nature.”

Now you know the tricks. Your move.