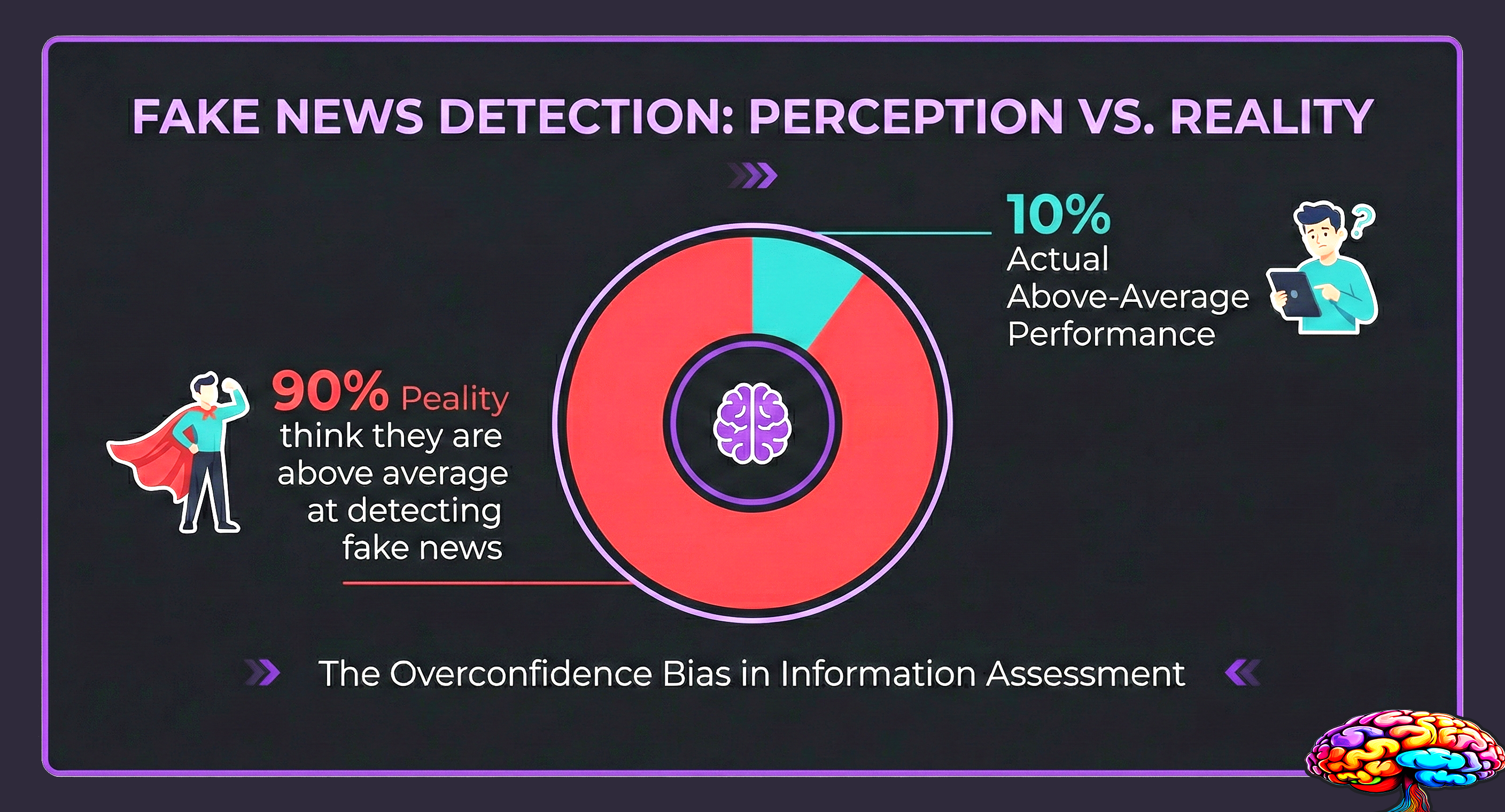

About 90% of Americans believe they’re “above average” at spotting fake news. That’s mathematically impossible, obviously. But here’s the part that should worry you.

The people who were most confident in their ability to detect misinformation? They were actually the worst at it. A study led by Ben Lyons at the University of Utah found that 75% of participants overestimated their fake news detection skills. And the most confident group performed below average.

This isn’t about being dumb. It’s about being human. Your brain has built-in shortcuts that make you vulnerable to false information. And the smarter you are, the better you might be at fooling yourself.

Your Brain Prefers Comfortable Lies to Inconvenient Facts

Here’s something most people don’t realize. Your brain wasn’t built to find the truth. It was built to keep you alive and help you belong to a group. Truth is just a bonus.

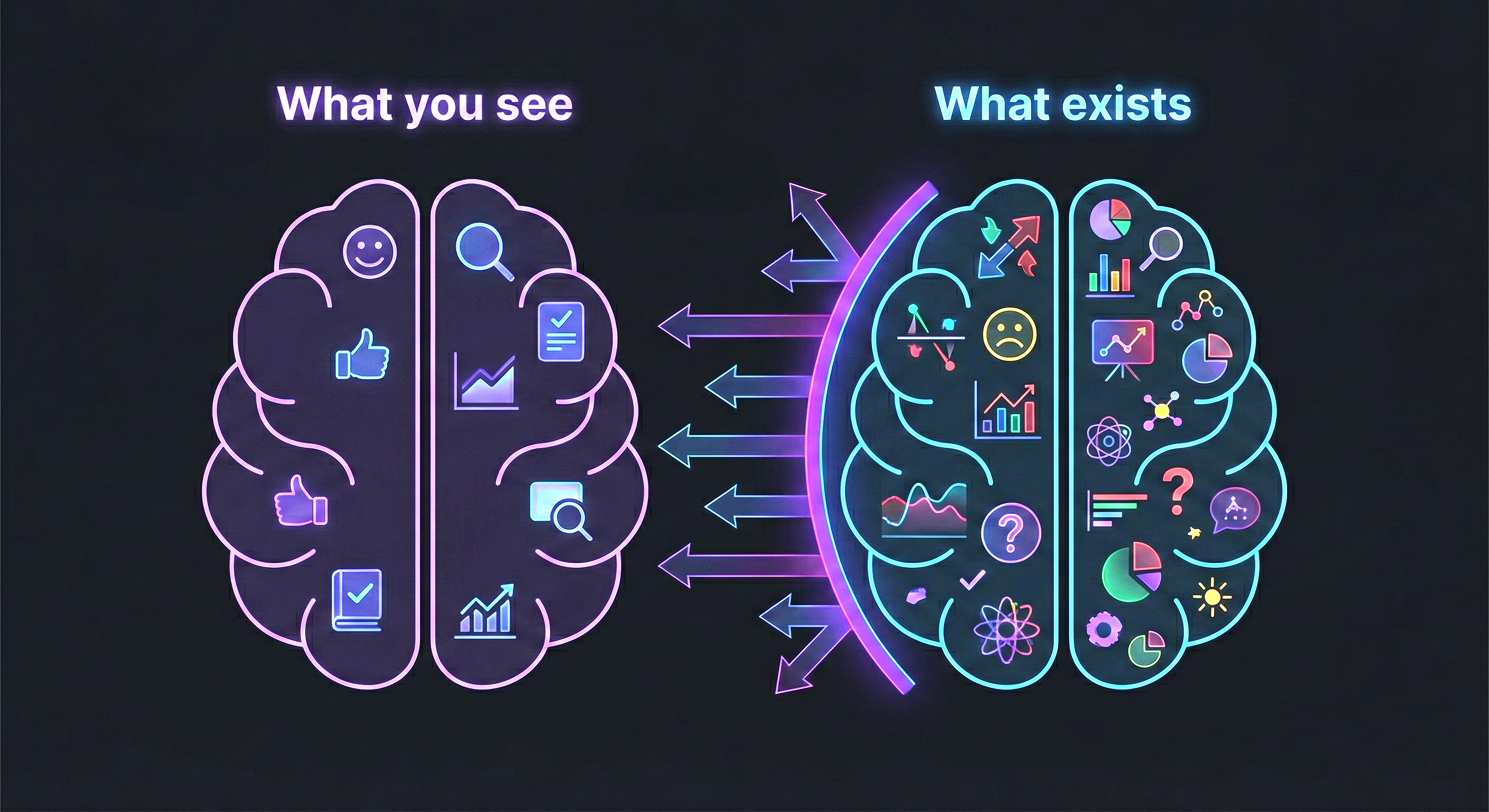

That’s why confirmation bias is so powerful. It’s one of several cognitive biases that quietly sabotage your everyday decisions. It’s the tendency to pay attention to information that supports what you already believe. And to ignore or dismiss anything that challenges it.

Researchers have even measured this with eye-tracking technology. In one study, participants’ eyes literally avoided looking at political ads that contradicted their beliefs. They spent more time looking at ads that matched their views. Your brain is filtering reality before you’re even aware of it.

Truthiness Beats Truth

Comedian Stephen Colbert coined the term truthiness back in 2005. It means “truth that comes from the gut, not books.” Merriam-Webster made it the Word of the Year in 2006.

But truthiness isn’t just a joke. It describes how most of us actually process information. We go with what feels right instead of what is right. As psychiatrist Joe Pierre puts it, we’ve replaced objective evidence with the self-satisfaction of confirmation bias.

- We prefer opinions over peer-reviewed research

- We choose “alternative facts” that match our worldview

- We trust our gut feelings more than actual data

- We judge evidence as “good” when it supports us and “bad” when it doesn’t

“It is effortful and difficult for our brains to apply existing knowledge when encountering new information. When new claims are false but sufficiently reasonable, we can learn them as facts. Thus, everyone is susceptible to misinformation to some degree.” — Researchers at UCSF

Recommended read: False by Joe Pierre MD — A deep dive into why mistrust, disinformation, and motivated reasoning make us believe things that aren’t true.

Why Education Doesn’t Protect You Like You Think

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable. You’d think that more education would make people better at spotting fake news. But research tells a different story.

A study by psychologist Dan Kahan at Yale found something surprising. Religious people were far more likely to agree that humans developed from earlier species. But only if the statement started with “according to the theory of evolution.” That qualifier let them answer accurately without threatening their religious identity.

Identity Beats Intelligence

Motivated reasoning takes confirmation bias a step further. It’s not just passively favoring information you agree with. It’s actively reinterpreting evidence to protect your identity and your group’s beliefs. This is exactly why people refuse to change their political beliefs, even when confronted with clear evidence.

Here’s a classic example from 1977. Sixty-seven psychologists reviewed fake experiments that used identical methods but different theoretical frameworks. The psychologists rated the experiments much more favorably when they supported their own preferred framework.

Scientists. Trained in critical thinking. Still biased by their own identity.

| What You’d Expect | What Actually Happens |

|---|---|

| More education = better at spotting lies | Education doesn’t override identity biases |

| Smart people question everything | Smart people are better at rationalizing their biases |

| Scientists are objective | Scientists favor studies matching their own framework |

| Political knowledge helps | Heavy news consumers are more inaccurate on political claims |

| Confidence means competence | The most confident fake news detectors perform the worst |

A 2024 study had Democrats and Republicans evaluate both false and factual news headlines. Strong political bias persisted across all education levels. The most biased individuals? Those who believed their own political group was unbiased and objective.

Sociologist Matthew Facciani calls this the identity trap. “People who reject evidence are often not naive or ignorant,” he writes. “Instead, their rejection of evidence is a rational, if unconscious, choice to defend the values associated with meaningful identities.”

Recommended read: Misguided by Matthew Facciani — Explains how our social networks and political identities blind us to false claims.

The Tricks That Make Fake News Feel True

Fake news doesn’t succeed because people are stupid. It succeeds because it exploits specific psychological vulnerabilities that all of us share.

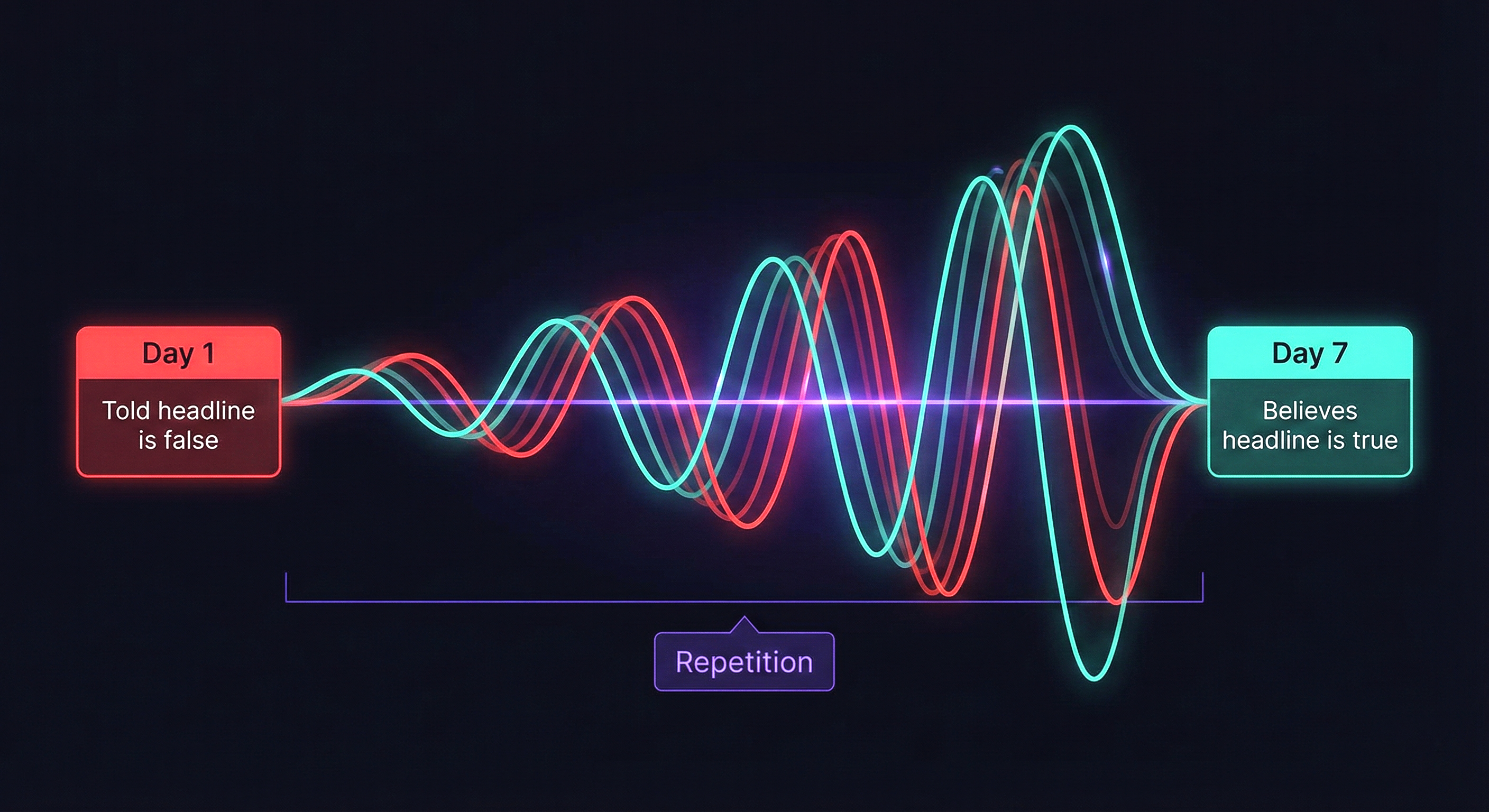

The Illusory Truth Effect

The illusory truth effect is one of the most dangerous. Simply showing someone the same information over and over increases the chance they’ll believe it. Even if they’ve been told it’s false.

In a 2018 study, researchers had participants read fake news headlines. Then they told the participants that fact-checkers had flagged these headlines as false. A week later, participants were more likely to believe those headlines were true. Not less.

Why? Because your brain interprets familiarity as truth. Repeated content feels easier to process. And your brain misreads that ease as evidence that it must be real.

Cognitive Dissonance Makes You Double Down

Cognitive dissonance is the uncomfortable feeling you get when two of your beliefs conflict. And your brain will do almost anything to make that discomfort go away.

Social psychologist Leon Festinger studied a cult that predicted a world-ending flood on December 21, 1954. When the flood didn’t happen, the most socially connected members doubled down on the cult’s beliefs. The less connected members left.

This happens with misinformation too. When you’ve publicly shared or defended a false claim, admitting you were wrong threatens your identity. So your brain finds ways to justify the original belief instead.

- You dismiss the correction as biased

- You find new “evidence” to support the false claim

- You attack the credibility of the person correcting you

- You convince yourself the details don’t matter

“It’s useful to think of confirmation bias as the goggles we put on when we feel highly motivated by fear, anxiety, anger. In these states, we begin looking for confirmation that the emotions we feel are justified.” — David McRaney, author of You Are Not So Smart

Why You Probably Think You’re Immune (You’re Not)

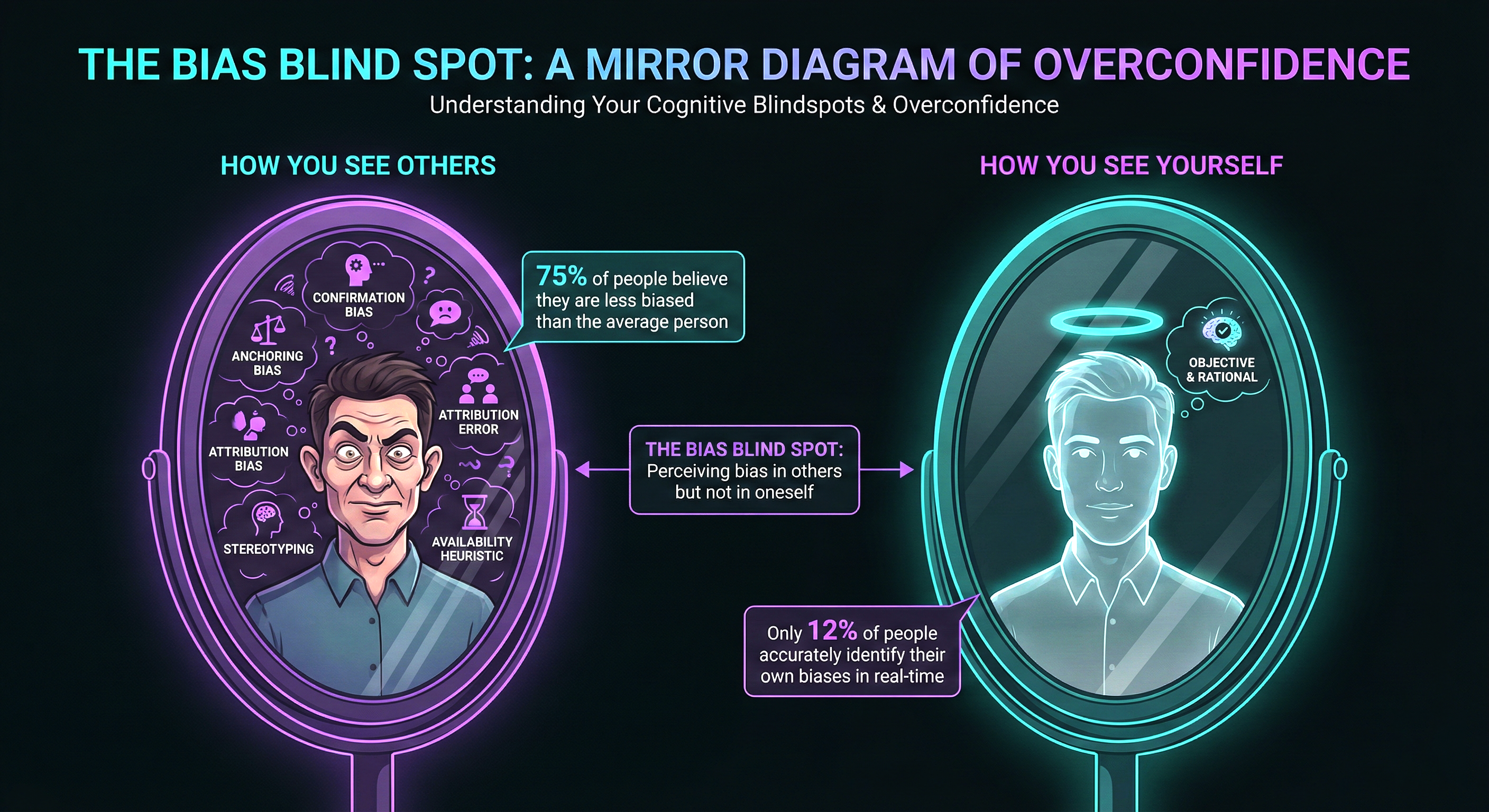

There’s a specific cognitive bias that makes all of this worse. It’s called the bias blind spot. You can easily see biases in other people. But you’re nearly blind to your own.

Remember that stat from earlier? About 90% of Americans thinking they’re above average at detecting fake news? That’s the bias blind spot in action.

The Overconfidence Trap

Psychologist John Petrocelli, who studies what he technically calls “the science of bullshit,” identified two powerful motivators that make us fall for false information:

- The need to belong. We accept information that helps us fit in with our group. Questioning it risks social rejection.

- The need for consistency. We’ve already committed to certain beliefs. Changing them feels like admitting we’re flawed.

In one clever experiment, researchers secretly changed participants’ political ratings to be more moderate. When shown their (manipulated) answers, most participants didn’t protest. They simply rationalized the moderate position as their own. One person who’d rated Clinton as far more experienced than Trump suddenly explained, “I think they’re both experienced in their field.”

Your Social Media Feed Makes It Worse

Social media doesn’t cause misinformation by itself. But it pours gasoline on every vulnerability listed above.

- Echo chambers reinforce confirmation bias by showing you more of what you already agree with. This is closely tied to why we follow the crowd, even when we know better

- Repetition triggers the illusory truth effect at scale

- Emotional content gets more engagement, so algorithms promote outrage over accuracy

- 0.1% of Twitter users shared over 80% of misinformation during the 2016 election

- People over 65 were seven times more likely to share fake news articles than the youngest age group

Research shows that people who get their news primarily from social media are more likely to hold conspiracy beliefs. But this was only true for people already attracted to conspiratorial thinking. Social media doesn’t create the vulnerability. It amplifies it.

Recommended read: The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli — A guide to the 99 most common cognitive errors we all make, from false consensus to hindsight bias.

How to Actually Protect Yourself from Misinformation

You can’t eliminate your biases. But you can learn to work around them. Here are evidence-based strategies that actually help.

-

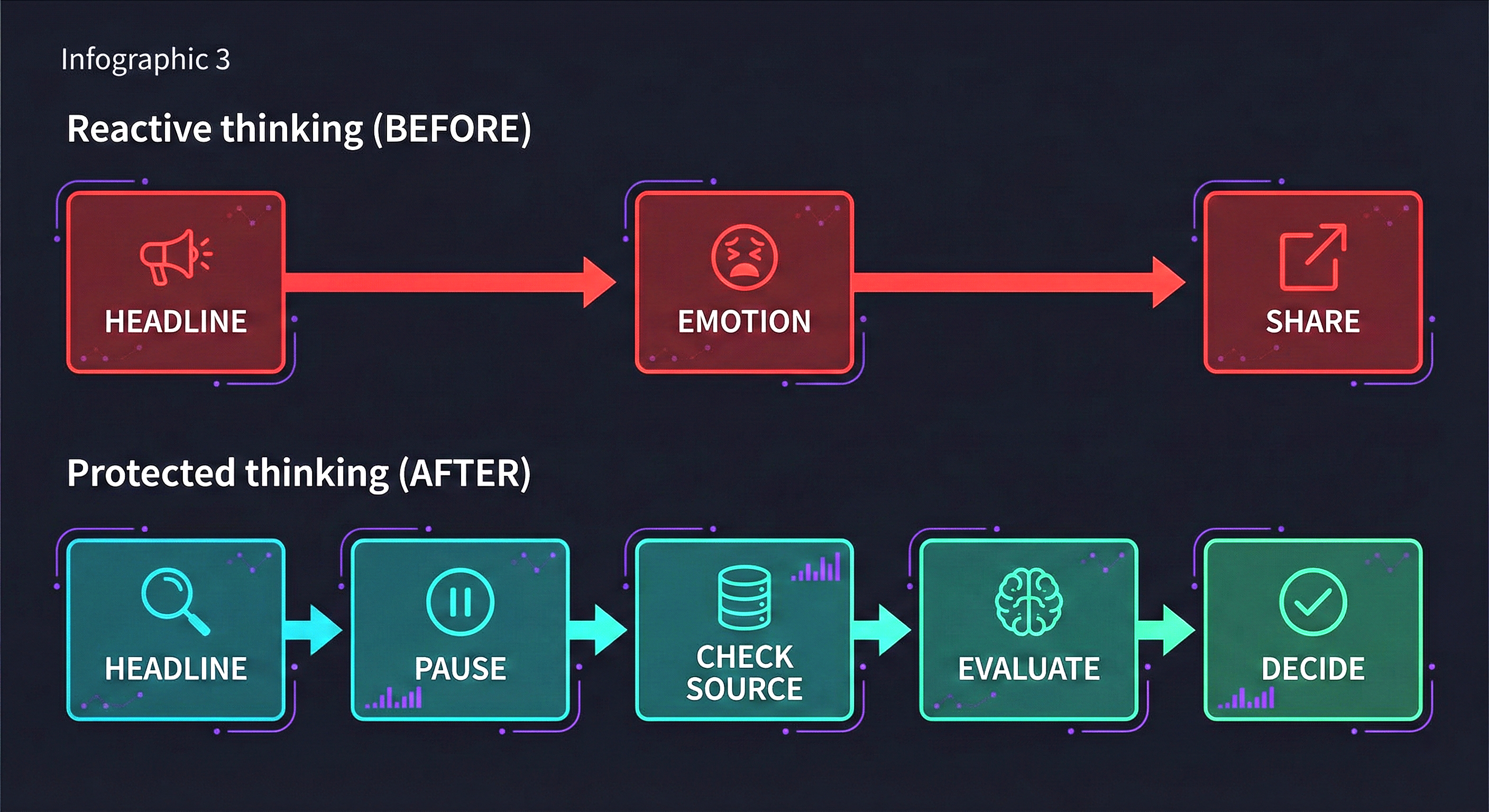

Slow down before sharing. Most misinformation spreads because people react to headlines without reading the article. 59% of links shared on X (formerly Twitter) are never even clicked. Just pausing to read reduces sharing of false news significantly.

-

Be extra skeptical of news that confirms your beliefs. This is counterintuitive. Your gut says “yes, obviously true.” That’s exactly when you should check the source. Confirmation bias is strongest when information matches your identity.

-

Try prebunking instead of debunking. Research on psychological “inoculation” shows that warning people about manipulation tactics before they encounter misinformation is more effective than correcting them afterward. Learn the common tricks, and you’ll spot them faster.

-

Check your emotional state. If a headline makes you feel angry, scared, or outraged, that’s a red flag. Fake news is designed to trigger strong emotions because emotional people don’t think critically. Take a breath before you react.

-

Question your identity attachment. Ask yourself: “Am I evaluating this evidence fairly, or am I protecting my group’s beliefs?” This simple question activates slower, more analytical thinking.

-

Diversify your information sources. If you only read news that agrees with your worldview, you’re building a stronger echo chamber. Deliberately seek out reputable sources from different perspectives.

Joe Pierre describes our vulnerability to misinformation as falling on a spectrum. On one end is extreme gullibility, where you believe everything. On the other is paranoid denialism, where you trust nothing. Both extremes make you easy to manipulate. The goal is finding the middle ground of healthy skepticism.

The uncomfortable truth is this. You will fall for misinformation at some point. Everyone does. The difference is whether you’re willing to admit it, update your beliefs, and keep your guard up. The people who think they’re immune are the ones most at risk.

Recommended read: Misguided by Matthew Facciani — Practical strategies for reducing misinformation’s influence, from personal conversations to rebuilding institutional trust.