A Boy Scout once approached psychologist Robert Cialdini outside a grocery store. The kid asked if Cialdini wanted to buy five-dollar tickets to a circus. Cialdini said no.

Then the boy asked, “Well, how about buying a couple of chocolate bars? They’re only a dollar each.”

Cialdini bought two. He doesn’t even like chocolate.

He walked away holding candy he didn’t want, wondering what just happened. That moment launched decades of research into something most of us never think about. There are hidden rules running in your brain that other people can trigger. And the people who know these rules use them on you every single day.

The Six Invisible Levers

Psychologist Robert Cialdini spent years going undercover. He trained as a car salesman, worked at fundraising organizations, and sat through countless sales pitches. What he discovered was striking. Nearly every persuasion attempt he encountered relied on the same six psychological principles.

These aren’t tricks that only work on gullible people. They work on almost everyone because they’re hardwired shortcuts your brain uses to make quick decisions. Here’s the lineup:

| Principle | What It Means | How It’s Used Against You |

|---|---|---|

| Reciprocity | You feel obligated to return favors | Free samples, gifts before a sales pitch |

| Liking | You say yes to people you like | Salespeople mirroring your interests |

| Authority | You trust experts and credentials | White coats in ads, celebrity endorsements |

| Social proof | You follow what others do | ”Bestseller” labels, customer reviews |

| Scarcity | You want what’s running out | ”Only 3 left!” and countdown timers |

| Consistency | You stick with past commitments | Small sign-ups that lead to big asks |

These six principles work because they usually steer us right. Following an expert’s advice is generally smart. Returning a favor keeps relationships healthy. The problem is that skilled persuaders can hijack these shortcuts to push you toward choices that benefit them, not you. This is exactly how people exploit your trust in everyday interactions.

“People say yes to those they owe. All human cultures teach this rule from childhood and assign punishing names to those who don’t give back.” - Robert Cialdini

Recommended read: Influence by Robert Cialdini. The foundational guide to understanding why we say yes and how to defend against manipulation.

The Small Yes That Leads to the Big Yes

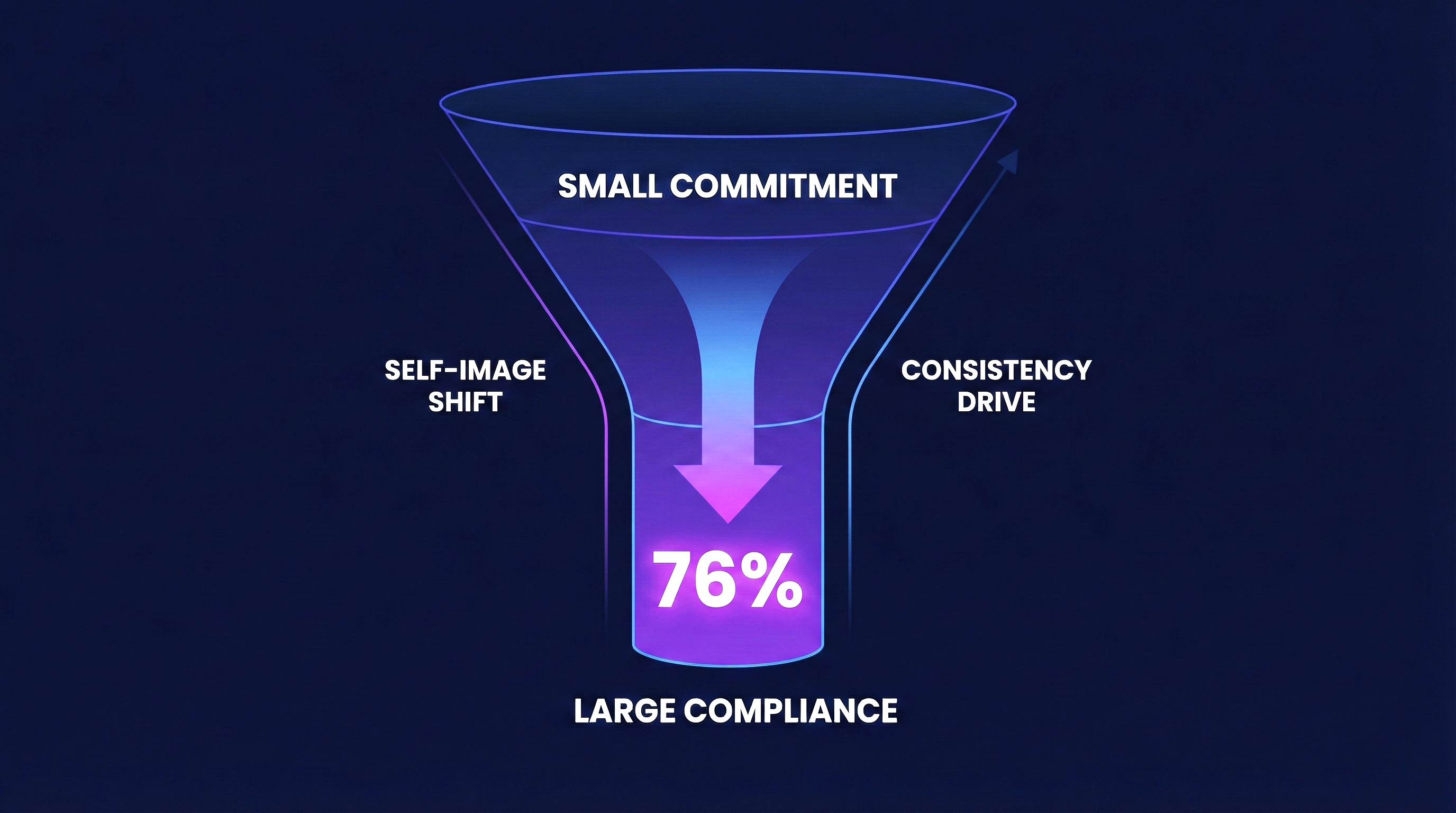

One of the sneakiest persuasion techniques doesn’t start big. It starts tiny. Researchers call it the foot-in-the-door technique, and it works by exploiting your need to stay consistent with your own actions.

The Billboard Experiment

In the 1960s, psychologists Jonathan Freedman and Scott Fraser ran a now-famous experiment. They went door-to-door in a California neighborhood and asked homeowners to install a massive, ugly billboard reading “DRIVE CAREFULLY” on their front lawns. Most people said no. A full 83% refused.

But one group was different. Two weeks earlier, a volunteer had visited their homes and asked them to display a tiny three-inch sign that read “BE A SAFE DRIVER.” Almost everyone agreed to that. It was so small, why wouldn’t they?

Here’s the shocking result. When the big billboard request came two weeks later, 76% of these people said yes. They went from accepting a tiny sticker to agreeing to block their entire front yard with an ugly sign.

It Gets Weirder

Freedman and Fraser tried another version. They asked a different group to sign a petition supporting “keeping California beautiful.” Everyone signed. Who’s against beauty? Then, two weeks later, they came back with the big DRIVE CAREFULLY billboard request. About half of these people agreed. Even though the petition had nothing to do with driving safety.

What happened? Signing that petition changed how these people saw themselves. They became, in their own minds, the kind of person who supports good causes. When the next request came along, they said yes to stay consistent with that self-image.

This is why salespeople start with small orders. The goal isn’t profit on that first sale. It’s commitment. Once you’re a customer, you’ll keep buying to stay consistent with your identity as their customer.

The Concession Game and Other Advanced Plays

The foot-in-the-door works by starting small. But there’s another technique that works in the exact opposite direction. It starts big on purpose.

Rejection Then Retreat

Remember Cialdini’s Boy Scout? The kid asked for five-dollar circus tickets first. When Cialdini said no, the boy “retreated” to a smaller request. Just a couple of chocolate bars.

This is the rejection-then-retreat technique. When someone makes a concession, your brain feels pressure to make one too. The boy gave up on the big ask. Now it’s your turn to give something back. So you say yes to the smaller request.

Research shows this method does something remarkable. People who agree through rejection-then-retreat are:

- More likely to actually follow through on their commitment

- More satisfied with the final arrangement

- More willing to agree to future requests

Why? Because they feel like they negotiated the outcome. They feel responsible for the deal. That sense of ownership makes the agreement stick.

The Lowball

Car dealerships perfected this one. A salesman offers you an incredible deal. Maybe $400 below competitors’ prices. You get excited. You fill out paperwork. You start telling friends about your new car. You might even drive it home for the night.

Then something “goes wrong.” The manager finds an error. The air conditioning wasn’t included. The trade-in was overestimated. The price creeps back up to exactly where the competition sits.

But here’s the thing. You’ve already decided this is your car. You’ve built mental support for that decision. New reasons to love the car have piled up. So when the original advantage disappears, you buy it anyway. Cialdini watched this play out over and over at a Chevrolet dealership where he trained undercover.

The lowball technique works because once you commit to a choice, your brain generates new reasons to justify it. Even if the original reason vanishes, those new justifications hold the decision in place.

Pre-suasion: Setting the Trap Before You Even Know It

Cialdini’s later research revealed something even more subtle. The most skilled persuaders don’t just pick the right message. They control what you’re thinking about before the message arrives.

He calls this pre-suasion. The idea is simple but powerful. If I can direct your attention to a specific concept right before I make my pitch, you’ll be more receptive to arguments that match that concept.

Here’s a real example. A grocery chain that played French music in the background sold more French wine. The music didn’t explicitly say “buy French wine.” It just primed shoppers to think about France. That was enough. Stores use dozens of tricks like this to manipulate your shopping brain without you ever noticing.

Pre-suasion explains why:

- Charities show you sad images before asking for money

- Salespeople ask about your family before selling life insurance

- Politicians wrap their message in patriotic symbols before asking for your vote

“Optimal persuasion is achieved only through optimal pre-suasion. To change minds, a pre-suader must first change states of mind.” - Robert Cialdini

Recommended read: Pre-Suasion by Robert Cialdini. A deeper look at how the moment before a message determines whether it succeeds.

When Persuasion Backfires: The Reactance Effect

Here’s something that surprises most people. Sometimes the harder you push, the more people resist. Psychologists call this psychological reactance. It’s your brain’s automatic pushback when it senses your freedom is being threatened.

Researcher Jonah Berger studied this phenomenon closely. He found that heavy-handed persuasion often produces the exact opposite of the intended result. A boomerang effect.

The evidence is everywhere:

- Anti-smoking campaigns aimed at teenagers sometimes increased smoking rates. Teens saw the warnings as an authority figure telling them what to do, and they pushed back.

- When doctors spoke in authoritative commands (“You need to follow this advice or things will get worse”), patients were slower to fill prescriptions and more likely to skip doses.

- Providing people with direct recommendations can make them choose the opposite just to assert their autonomy.

Why “Don’t Do This” Makes People Want to Do It

Reactance kicks in because people have a deep need to feel in control. When a message sounds like a command, it triggers a threat response. The person stops evaluating the message on its merits and starts defending their freedom to choose.

This is why the smartest persuaders don’t push at all. They remove barriers instead. Berger calls them catalysts. Instead of adding more pressure, they figure out what’s stopping someone from changing and they take that obstacle away.

- Instead of arguing harder, they let people convince themselves

- Instead of demanding compliance, they offer choices

- Instead of restricting options, they highlight what people already believe

Recommended read: The Catalyst by Jonah Berger. A practical guide to changing minds by removing roadblocks instead of pushing harder.

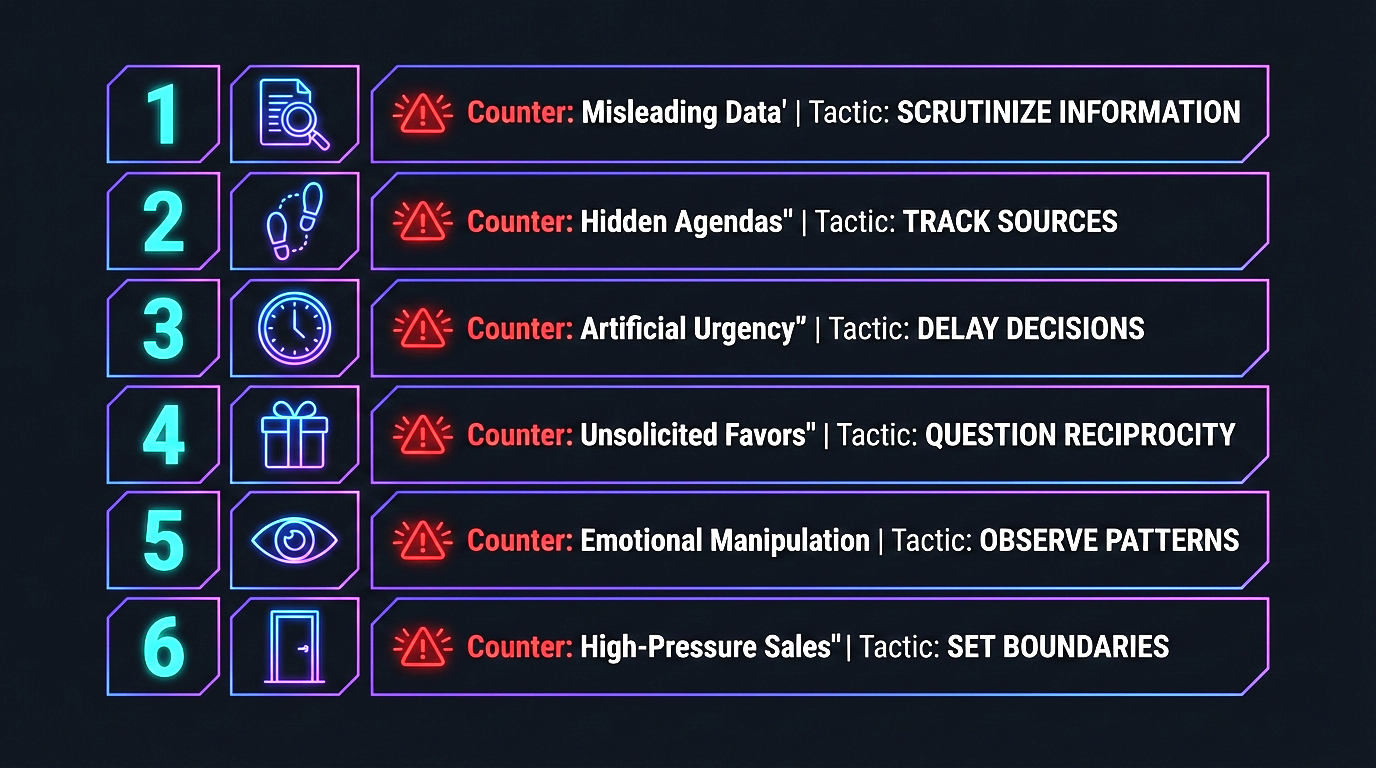

How to Defend Yourself

Now that you know the playbook, here’s how to use that knowledge as a shield. You don’t need to become suspicious of everyone. You just need to pause and ask the right questions when a decision feels oddly easy.

-

Separate the person from the offer. If you really like the salesperson, that’s a red flag, not a green one. Cialdini’s advice: ask yourself whether you’d still want the product if someone you didn’t like was selling it. Judge the deal, not the dealer.

-

Watch for the tiny first ask. If someone gets you to agree to something small, notice it. Ask yourself whether this small commitment is designed to lead somewhere bigger. Petition signatures, free trials, and quick surveys are all potential foot-in-the-door openers.

-

Question artificial scarcity. “Only 2 left!” and “This deal expires tonight!” are designed to short-circuit your thinking. These are classic dark patterns that trick your brain into rushed decisions. If the scarcity feels manufactured, it probably is. A good deal today will still be a good deal tomorrow.

-

Notice unsolicited gifts. Free samples, surprise favors, and “no strings attached” offers often do have strings. Recognize the obligation you feel and ask whether you’d make this choice without the gift.

-

Catch the pre-suasion setup. Pay attention to what’s being shown, played, or discussed right before the pitch. Background music, emotional images, and leading questions are all designed to put you in a specific state of mind before the real request arrives.

-

Resist the sunk cost pull. If the terms of a deal change after you’ve committed, treat it as a new decision. The lowball only works because you feel locked in. You’re not. Walk away and start fresh.

The Bottom Line

Every day, someone is using these techniques on you. Not because they’re evil. But because these methods work. Salespeople, marketers, politicians, fundraisers, and even friends and family use the principles of reciprocity, consistency, social proof, authority, scarcity, and liking to move you toward “yes.”

The good news? Awareness is the antidote. Once you can name what’s happening, the spell breaks. You don’t stop being a social human. You just stop being an easy target.

The next time a deal feels too good, a favor feels too generous, or a “yes” slips out before you’ve really thought about it, pause. Ask yourself which lever just got pulled. That single moment of recognition is worth more than any persuasion technique ever invented.