You’re sitting at a family dinner. Someone brings up politics. You share a fact. An actual, verified, well-sourced fact. And the person across the table doesn’t just disagree. They dig in harder.

You’ve been there. We all have. You walked away thinking, “How can they ignore the evidence?” But here’s the uncomfortable truth. They’re not ignoring it. Their brain is actively working against it. And yours does the exact same thing.

This isn’t about intelligence. It’s not about education. Some of the smartest people on earth hold beliefs that crumble under basic scrutiny. The reason has nothing to do with being dumb. It has everything to do with how your brain processes identity, belonging, and threat.

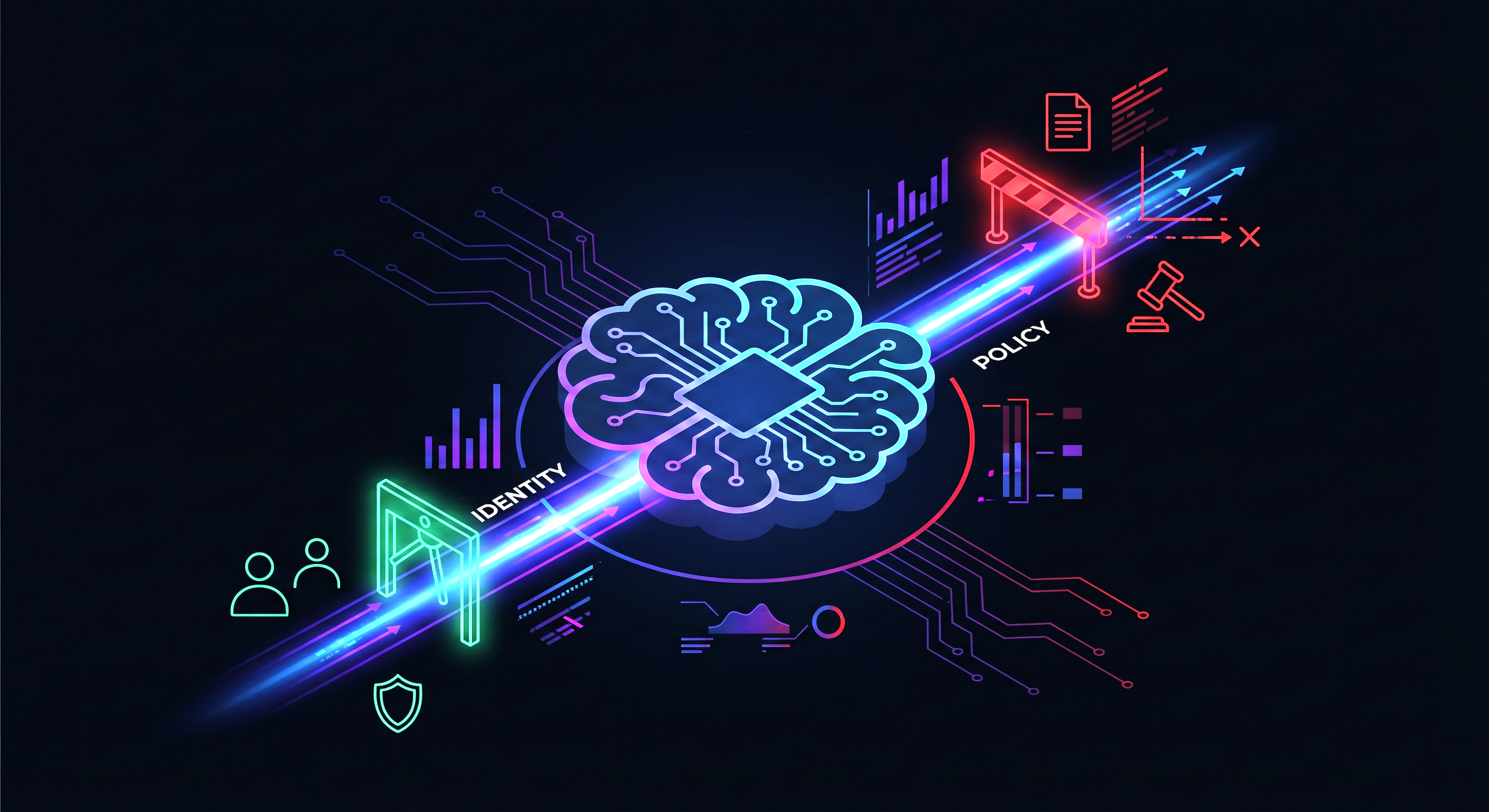

Politics Is Identity, Not Policy

Here’s a finding that should shake you. Researcher Lilliana Mason studied thousands of Americans and found that identity-based ideology, not policy positions, drives political behavior. She concluded that we’ve become “ideologues without issues.”

That means your political team matters more than your actual beliefs about healthcare, taxes, or immigration. You’re not voting for policies. You’re voting for who you are.

This goes deep. Consider this study from psychologist Geoffrey Cohen. He gave Yale students a fake newspaper article about a welfare plan. Some versions were generous. Others were strict. But here’s the twist. He also told students whether Republicans or Democrats supported the plan.

The result? Students based their opinions on which party backed it. Not on the actual policy details. When asked why they liked the plan, they made up reasons that had nothing to do with party loyalty. They genuinely believed their reasoning was independent.

- Political identity predicts beliefs better than actual policy knowledge

- People judge evidence as “good” when it supports their side and “flawed” when it doesn’t

- Brain imaging shows that self-referential brain regions activate when people evaluate political information, not the reasoning centers

- Both Democrats and Republicans show the same bias patterns. Neither side is immune

Neuroimaging research drives this home. When people read information that challenged their political beliefs, the parts of the brain linked to negative emotions lit up. The prefrontal cortex, your reasoning center, stayed quiet. Your brain treated a political challenge the same way it treats a personal attack.

“People do not necessarily systematically reason about strengths and weakness of offending information, but rather critique to reject it and protect the self.” — Adam Moore et al., Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society

Here’s what makes this worse. Making your political identity more visible actually increases the bias. One study found that conservatives who reflected on their conservative identity before answering questions about climate change became even more likely to deny it. But when people were asked to think about their national identity instead, both Democrats and Republicans became less polarized.

Your identity is a dial. The more you turn up the political identity, the more your brain filters out inconvenient evidence.

| What Drives Political Beliefs | How Strong Is the Effect |

|---|---|

| Party identity (team loyalty) | Very strong. Overrides policy details |

| Policy substance (actual issues) | Weaker than you think |

| Education level | Does NOT reduce political bias |

| Science literacy | Can actually increase bias on polarized topics |

That last row is important. Being well-educated doesn’t protect you. In fact, highly educated conservatives were even less likely to accept scientific consensus on climate change than less-educated ones. Education gives you better tools for rationalizing, not better tools for truth-seeking.

Recommended read: The Ideological Brain by Leor Zmigrod — A Cambridge neuroscientist reveals how ideologies physically reshape our brains and constrain flexible thinking.

The Mental Gymnastics Your Brain Does to Stay “Right”

Your brain has a favorite trick. It’s called motivated reasoning. And it works like this. You don’t evaluate evidence objectively. You evaluate it based on whether it supports what you already believe. This is one of the key reasons smart people still fall for fake news.

Princeton psychologist Ziva Kunda described it as “an attempt to be rational and to construct a justification of one’s desired conclusion.” You think you’re being logical. You’re not. You’re being a lawyer, building a case for a verdict you already decided.

Here’s how it plays out in the real world:

- You read a study that agrees with your politics. You think, “Great study. Solid methodology.”

- You read a study that disagrees. You think, “That study is flawed. The researchers must be biased.”

- You rate experts as credible when they agree with you and as “not really experts” when they don’t

- You do all of this unconsciously while believing you’re being perfectly objective

Psychologist Joe Pierre calls this identity protective cognition. Your brain isn’t trying to find truth. It’s trying to protect who you are. Motivated reasoning is just one of many cognitive biases quietly sabotaging your everyday decisions.

But there’s an even sneakier version of this. Dan Ariely’s research uncovered a phenomenon called solution aversion. It works like this. If you don’t like the proposed solution to a problem, your brain denies the problem exists.

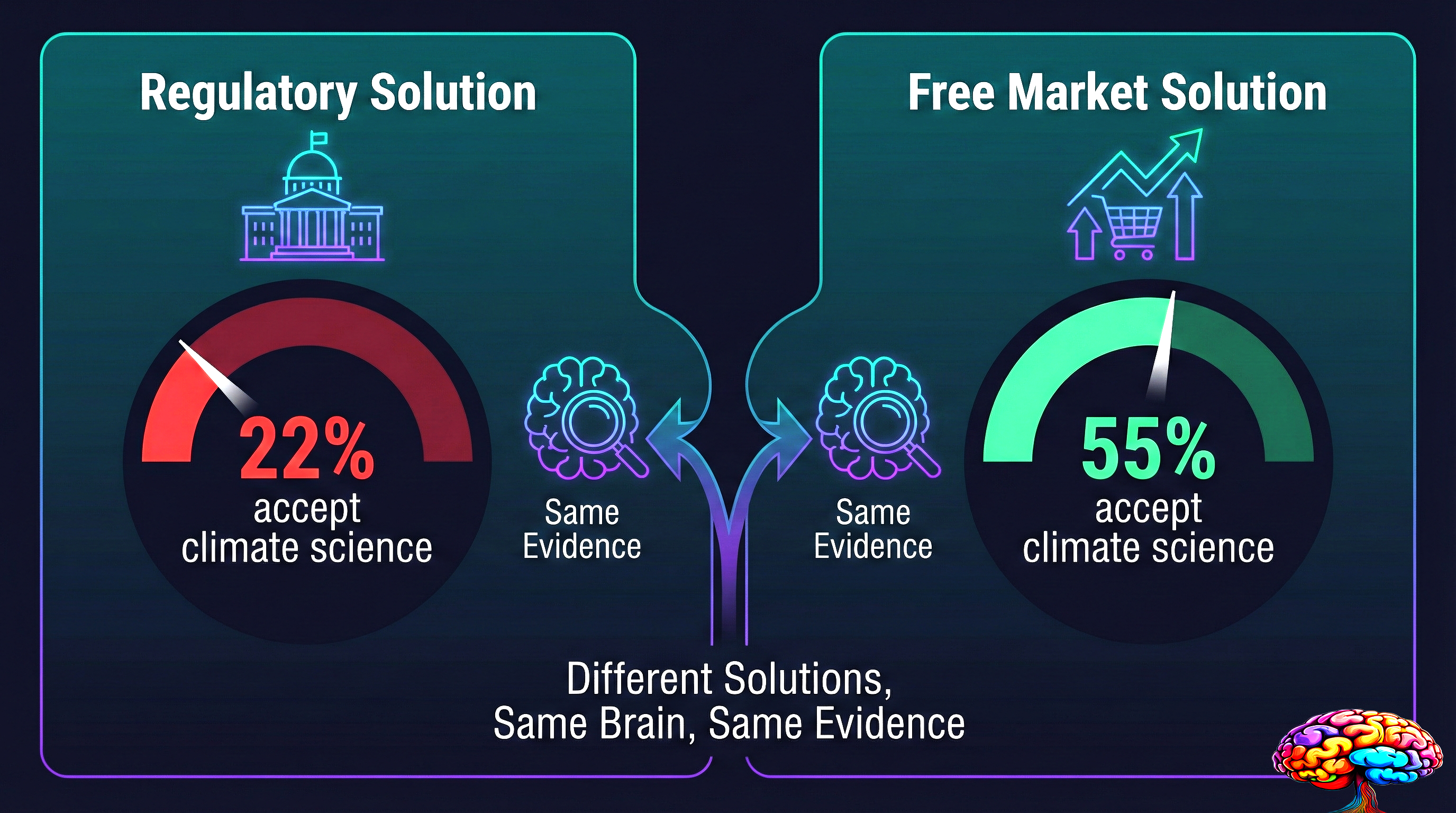

The Climate Change Experiment

Researchers gave conservative Republicans an article about climate change. For some, the article described regulatory solutions like government restrictions on fossil fuels. For others, it described free-market solutions.

Then they asked everyone, “Is man-made climate change real?”

- Only 22% of conservatives who read about regulatory solutions said yes

- But 55% of conservatives who read about free-market solutions said yes

Same science. Same evidence. Different solutions. The conservatives weren’t anti-science. They were anti-regulation. And their brains handled that discomfort by denying the problem altogether.

This happened with COVID too. People who opposed vaccines and lockdowns didn’t just disagree with the solutions. Many denied the virus was real. The brain’s logic goes: “I can’t accept the solution, so the problem must not exist.”

Recommended read: Misbelief by Dan Ariely — Explores how rational people end up believing irrational things through motivated reasoning, confirmation bias, and solution aversion.

How Your Tribe Controls What You Believe

You probably think you form your own opinions. But decades of research say otherwise. Your political tribe has more influence over your beliefs than you realize.

The classic Asch conformity experiments from the 1950s showed this clearly. Participants were asked to match line lengths. Easy task. People got it right nearly every time when alone. But when surrounded by actors who confidently chose the wrong answer, 75% of participants caved on at least one question. This tendency to follow the crowd shows up in nearly every area of life, not just politics.

They knew the answer was wrong. They said it anyway. And when asked about it later, they made up excuses for their “mistake” instead of blaming social pressure.

Now scale that to politics. You’re not just surrounded by a few actors in a lab. You’re surrounded by:

- Your social media feed, algorithmically tuned to show you what your tribe believes

- Cable news channels that shift their coverage to match what their audience demands

- Family and friends who share articles reinforcing the group narrative

- Online communities where dissent gets you mocked or banned

Cass Sunstein, author of Conformity, puts it this way. Two forces drive conformity. First, what other people believe gives you information about what’s true. Second, you want to stay in their good graces. Both forces push you toward your tribe’s consensus.

The Internet Made It Worse

Social media creates what Michael Morris, author of Tribal, calls amplified prevalence signals. When you scroll through your feed and see 50 people from your political group sharing the same opinion, your brain registers that as evidence. “Everyone thinks this, so it must be right.”

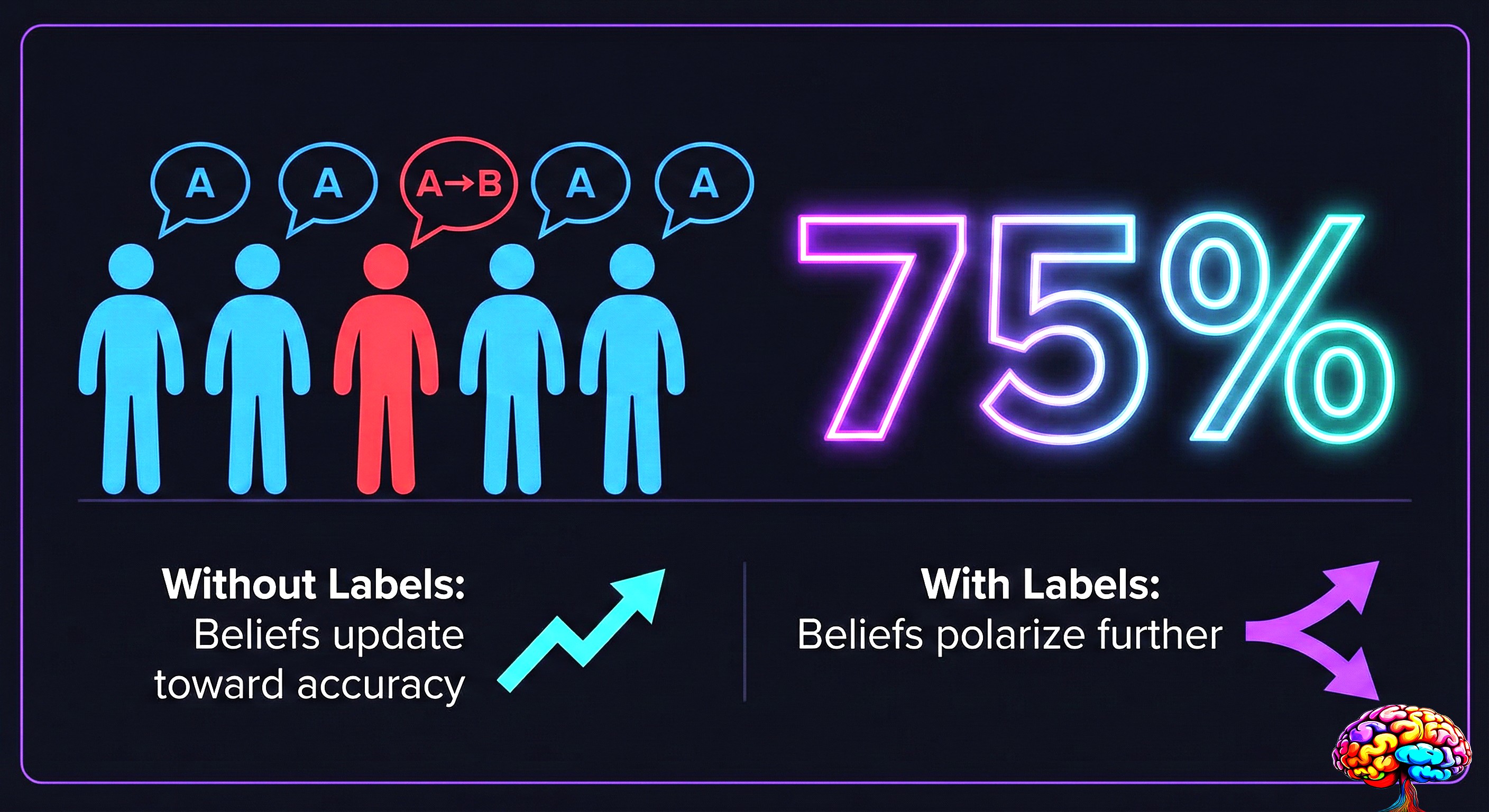

But here’s the key insight from Morris’s research. When people communicated with a politically diverse group without knowing party affiliations, their estimates became more accurate. They actually learned from each other. But when party labels were visible, the learning stopped. Defenses went up.

- Without labels: People updated beliefs toward accuracy

- With labels: People dug in and polarized further

- Conversations about non-political topics (“describe a perfect day”) were more effective at reducing bias than political debates

- The more salient your political identity, the less you learn from the other side

“People are also pliable when a prevalence signal comes from the behavior of their own party.” — Michael Morris, Tribal

This is why political arguments on social media almost never change minds. The tribal signals are too strong. The labels are too visible. Your brain goes into defense mode the moment it sees a red or blue flag.

Recommended read: Foolproof by Sander van der Linden — A Cambridge psychologist explains how misinformation infects our minds and what actually works to build psychological immunity.

Rigid Thinking Leads to Rigid Beliefs

Here’s something most people don’t know. Your tendency to hold onto political beliefs connects to how your brain handles simple, non-political tasks.

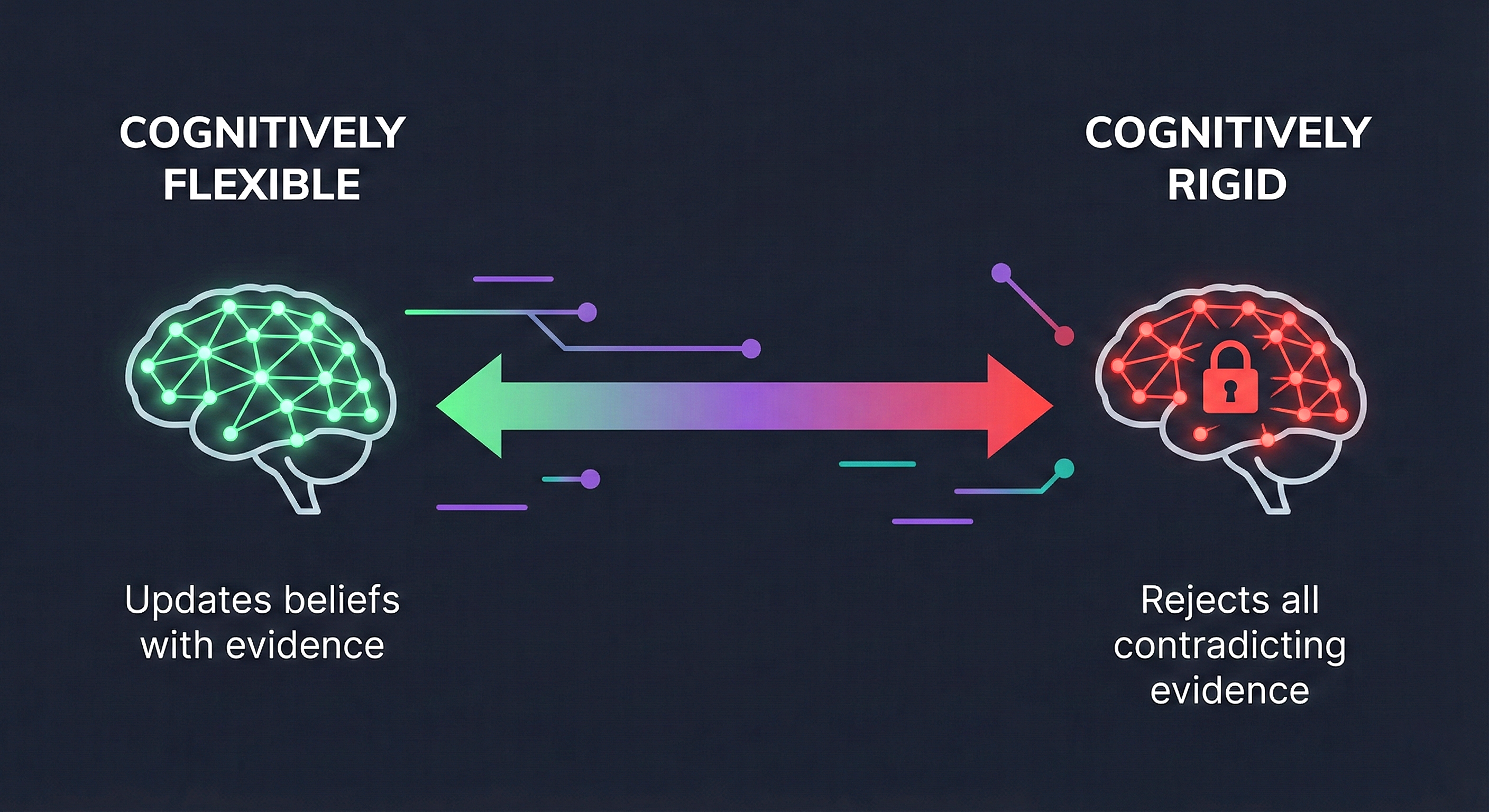

Leor Zmigrod, a neuroscientist at Cambridge, has spent years studying what she calls the ideological brain. Her research reveals something surprising. People who struggle to switch strategies on basic cognitive tasks (like sorting colored shapes by changing rules) also tend to hold the most dogmatic political views.

In other words, cognitive rigidity translates into ideological rigidity. A brain that has trouble adapting to new rules in a card game also has trouble adapting to new political evidence.

This isn’t about intelligence. Cognitively rigid people can be very smart. They just process information in a way that resists change. And they often don’t know it. A rigid person might insist they’re “spectacularly flexible.” We rarely understand our own thinking patterns.

Zmigrod describes ideologies as “sealed universes” that curve back on themselves. They repel evidence. They resist interrogation. And they do something even more concerning. They reshape the brain itself.

- Rigid ideological thinking changes how you perceive even neutral information

- The effects show up on brain scans even when you’re not thinking about politics

- Repetitive ideological rituals and rules strengthen certain neural pathways while alternative associations decay

- Dogmatism and intellectual humility sit at opposite ends of the same spectrum

The Dogmatism Spectrum

| Trait | Dogmatic Thinker | Intellectually Humble Thinker |

|---|---|---|

| Response to new evidence | Rejects or ignores | Considers and integrates |

| View of disagreement | Personal attack | Opportunity to learn |

| Comfort with ambiguity | Very low | High |

| Response to being wrong | Doubles down | Updates beliefs |

| Relationship with identity | Beliefs = self | Beliefs are held, not who I am |

As political thinker Eric Hoffer observed, “There is a certain uniformity in all types of dedication, of faith, of pursuit of power, of unity and of self-sacrifice.” It doesn’t matter if the ideology is left-wing or right-wing. The psychological mechanism is the same. Rigid thinking fuels rigid belief, regardless of what that belief contains.

How to Actually Change Minds, Including Your Own

So if facts don’t work, what does? The research actually offers some hope. But the strategies are counterintuitive.

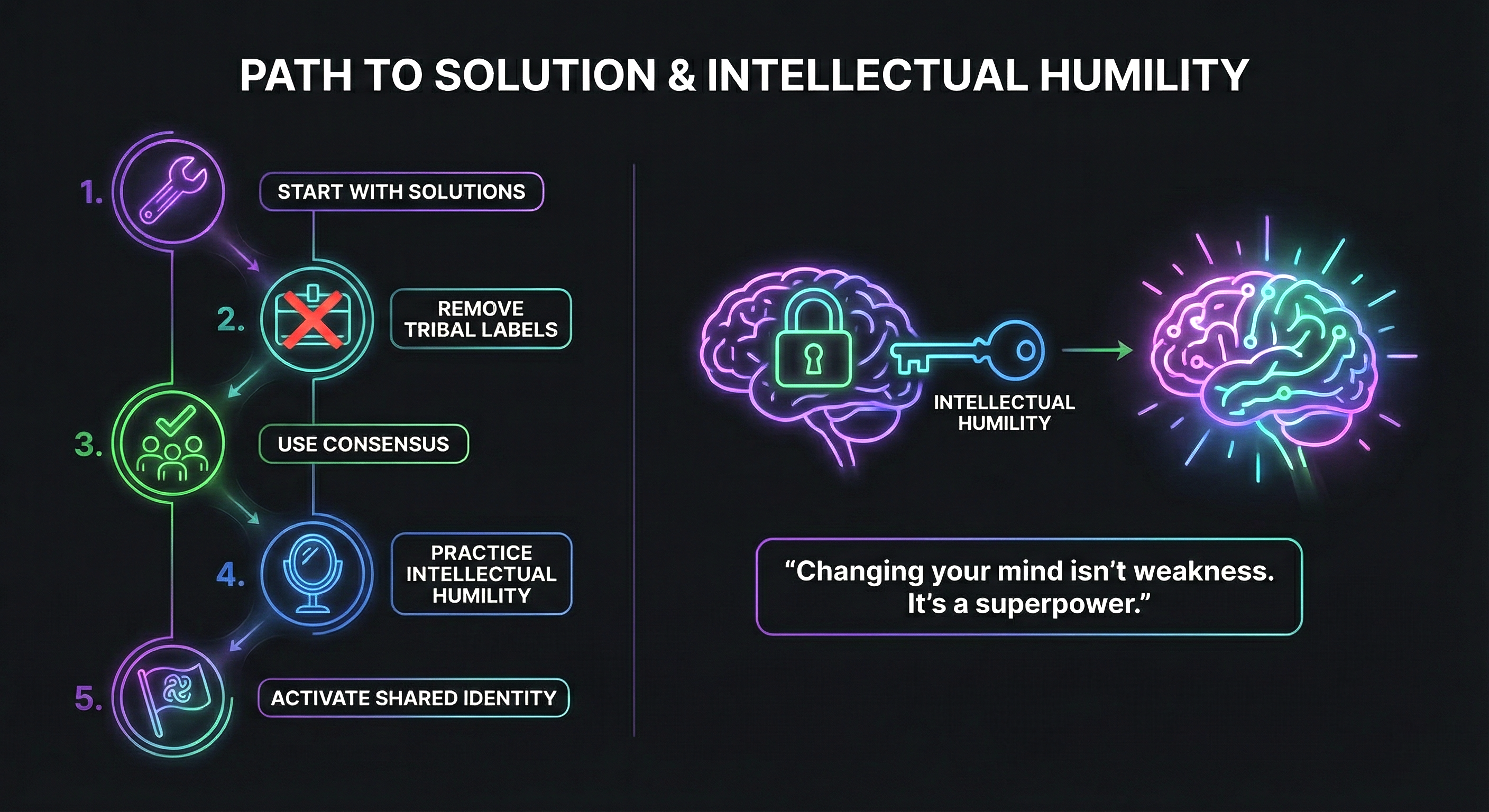

-

Start with solutions, not problems. Dan Ariely’s research on solution aversion shows that people are more open to acknowledging a problem when the proposed solutions align with their values. If you want someone to accept climate science, don’t lead with regulations. Lead with market-based solutions. Let them accept the problem on their own terms.

-

Remove the tribal labels. Michael Morris’s research found that cross-party conversations work better when people don’t know each other’s party. Start with non-political common ground. Talk about food, hobbies, or daily life first. Build human connection before touching politics.

-

Use consensus, not confrontation. Sander van der Linden’s research showed that telling people “97% of climate scientists agree” moved conservatives, liberals, and moderates alike toward the evidence. No backfire. Consensus messaging works because it sends a prevalence signal that doesn’t trigger tribal defenses.

-

Practice intellectual humility yourself. Before trying to change someone else’s mind, ask yourself: “When was the last time I changed mine?” If you can’t remember, you might be just as rigid as the person you’re arguing with.

-

Make national identity more salient than political identity. Research showed that when partisans reflected on their national identity instead of their party identity, polarization dropped. Reminding people of shared belonging reduces the tribal defenses.

Here’s the uncomfortable takeaway. You’re not immune to any of this. Your brain does the same motivated reasoning. Your tribe influences your beliefs the same way. The difference isn’t being smarter or more informed. It’s being willing to notice when your brain is protecting your identity instead of seeking truth.

Matthew Facciani, who studies misinformation at the intersection of identity and cognition, found that “the most biased individuals were those who believed their political group was unbiased and objective.” The people most trapped by tribal thinking are the ones who think they’re above it.

Recommended read: Misguided by Matthew Facciani — A clear-eyed look at how misinformation starts with our identities and social connections, with practical strategies for fighting back.

The next time you feel certain about a political belief, pause. Ask yourself whether you believe it because of evidence. Or because your tribe does.

That moment of doubt? That’s not weakness. Science actually celebrates changing your mind when the evidence demands it. As the research makes clear, modifying your beliefs based on evidence isn’t a shortcoming. It’s a superpower.