In 2014, Microsoft’s CEO sent an internal memo with a blunt warning. “The true scarce commodity,” he wrote, “is increasingly human attention.”

He wasn’t talking about some future trend. He was describing the business model that already powered the entire internet. And it wasn’t slowing down. It was accelerating.

You’ve probably heard that “if the product is free, you’re the product.” But that phrase doesn’t go far enough. You’re not just the product. Your attention is the raw material. Your eyeballs are the commodity. And your focus is being bought, sold, and traded in a market worth hundreds of billions of dollars every single year.

This isn’t about individual app design tricks. This is about an entire economic system built on extracting the most valuable thing you have.

The Business Model That Ate the World

To understand why your phone is so hard to put down, you have to understand the economics behind it. Not the psychology. The money.

Every tech company that offers you a “free” service faces the same basic problem. They need to make money. And there are really only two ways to do it. They can charge you directly for the product. Or they can give you the product for free, capture your attention, and sell that attention to advertisers.

The Fork in the Road

Tim Wu, a Columbia University professor who coined the term “net neutrality,” traces this choice all the way back to the 1800s. In his book The Attention Merchants, he shows how the first penny newspaper discovered something revolutionary. Give people content for almost nothing. Then sell their attention to someone else.

Google faced this exact fork in the road in the early 2000s. Its founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, had built the best search engine in the world. But they were burning through cash with no business model.

Page had actually warned against advertising. He wrote that “advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.” He was right. But the advertising model was too profitable to resist.

Here’s what happened next:

- Google chose ads. It became worth over $1 trillion.

- Facebook chose ads. It became worth hundreds of billions.

- YouTube chose ads. It became one of the most watched platforms on earth.

- Twitter chose ads. It turned 140 characters into a global attention machine.

Every single one of these companies makes money the same way. They capture your attention and resell it. That’s it. That’s the whole business.

“Every day, millions upon millions of people lean forward into their computer screens and pour their wants, fears, and intentions into the simple colors and brilliant white background of Google.com.” - John Battelle, co-founder of Wired

Recommended read: The Attention Merchants by Tim Wu. The definitive history of how industries have competed for human attention from newspapers to social media.

The Arms Race for Your Eyeballs

Here’s the part most people miss. The attention economy isn’t stable. It’s an arms race. And it’s getting more aggressive every year.

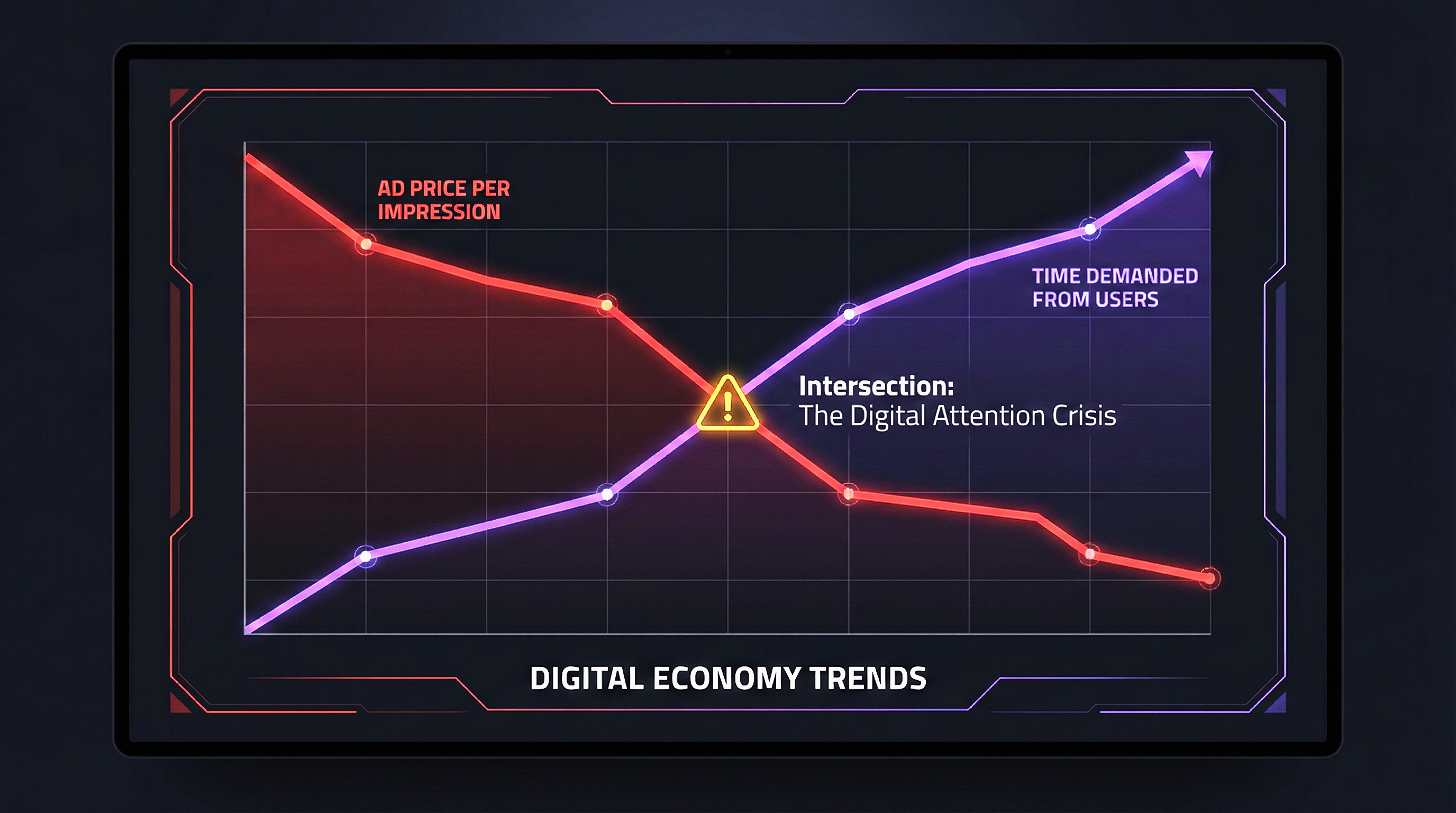

Advertising’s value is attention. When your eye flicks over a banner ad, the platform sells that moment to Toyota or Nike for about a penny. But Toyota’s ad budget is fixed. And the total amount of human attention in the world is also fixed. There are only so many waking hours in a day.

So what happens when more and more platforms compete for the same pool of attention? The price of each ad impression drops. And as the price drops, platforms have only one option to survive. Capture more attention. More users. More time on site. More scrolling.

The Squiggle Chart Economy

Max Fisher, a New York Times investigative reporter, describes how Silicon Valley investors created this monster. He calls it the “squiggle chart” model.

Here’s how it works:

- A startup builds a free service that attracts millions of users

- Investors pour in money based on user growth, not profits

- The company’s valuation skyrockets on pure speculation

- Eventually, someone has to turn all those users into actual revenue

- The only way to do that? Sell ads. Which means sell attention.

The numbers are staggering. A $250,000 investment in Instagram in 2010 turned into $78 million when Facebook bought the company just two years later. That kind of return creates a feeding frenzy. And every startup chasing those returns is competing for the same finite resource. Your focus.

| Factor | What It Means for You |

|---|---|

| Ad prices are dropping | Platforms must grab MORE of your time to make the same money |

| User growth is slowing | Platforms squeeze existing users harder with aggressive algorithms |

| Investor pressure is rising | Companies prioritize engagement over your wellbeing |

| Competition is intensifying | Every platform escalates tactics to steal attention from rivals |

| AI is getting smarter | Algorithms learn your weaknesses faster than you can build defenses |

“I felt like there could be an ‘emperor has no clothes’ vibe at times in startup funding. How far along could this insane valuation be perpetuated before someone had to actually write a check?” - Renee DiResta, former venture capitalist

Recommended read: The Chaos Machine by Max Fisher. The gripping inside story of how Big Tech’s race for engagement fractured the world.

When the Machine Takes Over

At some point, the task of capturing human attention became too complex for humans to manage. The companies handed the job to algorithms. And that’s when things got really dark.

Why Algorithms Love Outrage

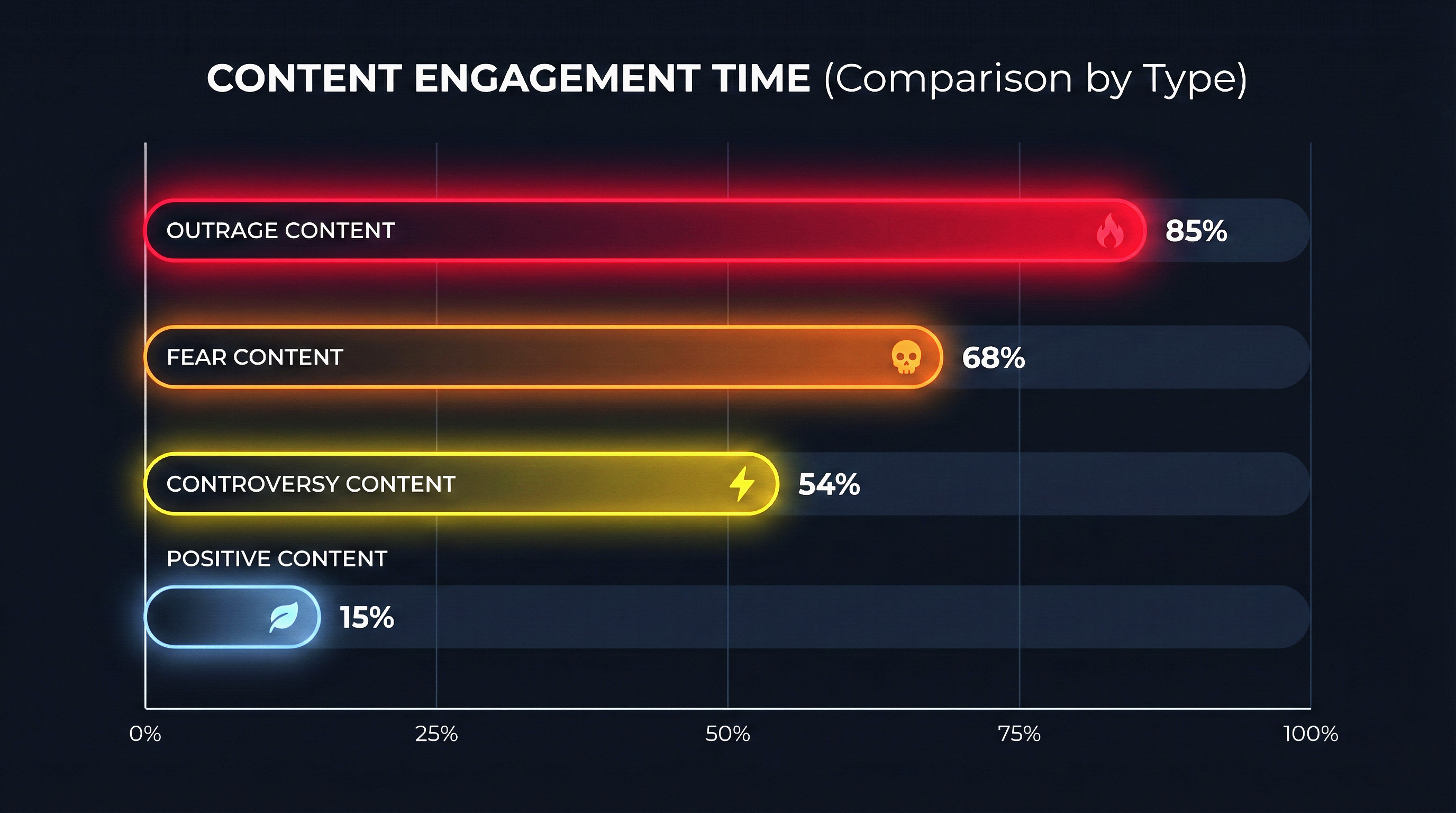

The algorithms that control your social media feed have one job. Keep you looking at the screen. They don’t care how. And they discovered something important about human psychology.

We stare at negative, outrageous content for much longer than we stare at positive, calm content. This is the same dopamine loop that apps use to hijack your brain’s reward system.

This is what Johann Hari, author of Stolen Focus, calls the core perversion of the system. The algorithm doesn’t want to make you angry. It doesn’t have feelings. But anger keeps you engaged. So the algorithm feeds you more of it.

Here’s what that looks like in practice:

- Posts that trigger moral outrage get more shares and comments

- Content that makes you anxious or fearful keeps you scrolling longer

- Conflict and controversy generate more engagement than agreement

- The algorithm amplifies whatever gets the strongest reaction, regardless of truth

James Williams, a former senior Google strategist who left the company to study attention at Oxford, compares this to a “denial-of-service attack” on the human mind. “We’re that server,” he says, “and there’s all these things trying to grab our attention by throwing information at us. It undermines our capacity for responding to anything.”

The Attention Tax on Society

This isn’t just a personal problem. It’s a civilizational one. When the attention economy fragments everyone’s focus, it undermines our collective ability to solve big problems.

Williams wrote something that stuck with me: “The liberation of human attention may be the defining moral and political struggle of our time. Its success is the prerequisite for the success of virtually all other struggles.”

Think about it. Climate change, public health, inequality. These are solvable problems. But solving them requires sustained focus, honest conversation, and clear thinking. The attention economy delivers the opposite. Fragmentation, outrage, and confusion.

“A digital detox is not the solution, for the same reason that wearing a gas mask for two days a week outside isn’t the answer to pollution.” - James Williams, former Google strategist

Recommended read: Stolen Focus by Johann Hari. A powerful investigation into why our attention is collapsing and who profits from the crisis.

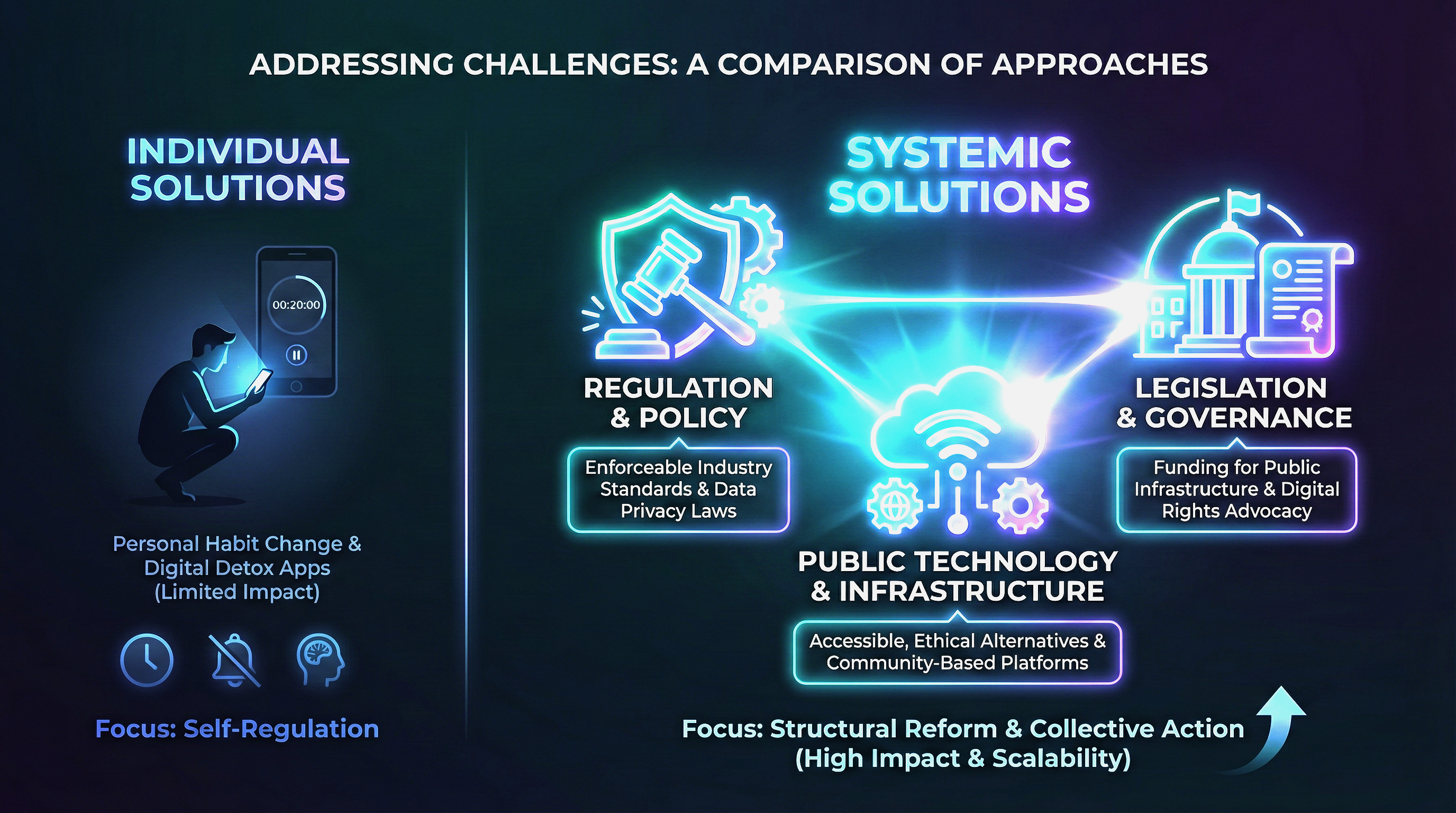

Fighting a System, Not Just a Habit

This is where most advice about digital distraction falls short. You get told to put your phone in a drawer, set a timer, or do a “digital detox.” And those things can help in the short term. But they miss the real problem.

Johann Hari makes a comparison that changed how I think about this. He points to the story of lead poisoning in American cities. For decades, kids were getting sick from lead paint and leaded gasoline. And the response? Blame the parents. Tell mothers to dust their homes more. Tell families to wash their hands better.

None of it worked. You know what did work? Ordinary citizens banding together to demand their governments ban lead from paint and gasoline. The problem was environmental, not individual.

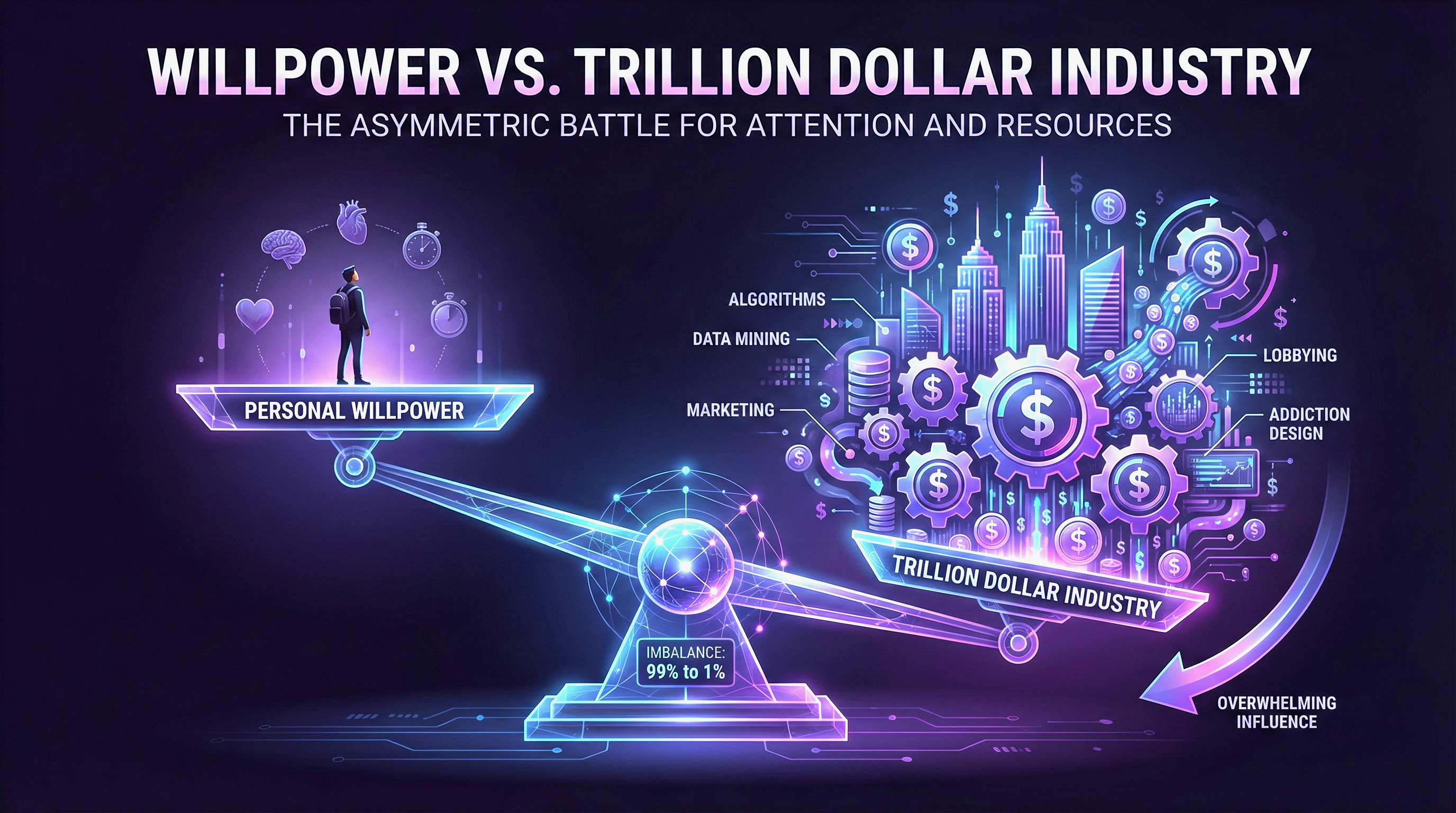

Our attention crisis works the same way. You can’t out-willpower a trillion-dollar industry that employs thousands of the smartest engineers on earth to keep you scrolling.

What Actually Needs to Change

Here’s what systemic solutions could look like:

-

Ban surveillance advertising. The entire business of surveillance capitalism turns your data into the product. If companies can’t track your behavior to sell hyper-targeted ads, the incentive to maximize your screen time drops dramatically.

-

Regulate algorithmic amplification. Platforms should be required to show you what you asked for, not what their engagement algorithms predict will keep you hooked.

-

Support public interest technology. We need alternatives to the ad-funded model. Think of it like public broadcasting for the internet age.

-

Protect children by law. Kids can’t consent to having their attention harvested. Age verification and strict limits on addictive design for minors should be non-negotiable.

-

Fund attention literacy. Schools should teach how the attention economy works. When you understand the game, you’re harder to exploit.

That said, individual action still matters. Not because it solves the problem alone, but because awareness is the first step toward demanding change.

- Use ad blockers. James Williams calls them “one of the few tools that we as users have if we want to push back against the perverse design logic that has cannibalized the soul of the Web.”

- Pre-commit to limits. Hari uses a kSafe, a timed lockbox for his phone. You can use app timers, screen time settings, or physical barriers.

- Audit your feeds. Unfollow accounts that exist only to provoke outrage. The algorithm feeds on your reactions. And watch out for dark patterns that trick your brain into clicking, subscribing, or sharing things you never intended to.

- Talk about it. The more people understand this system, the harder it becomes to maintain.

Recommended read: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff. The groundbreaking book that named the economic system turning your behavior into profit.

Your Focus Is Worth Fighting For

Here’s the uncomfortable truth. The attention economy won’t fix itself. The incentives are too strong. The profits are too massive. And the companies involved are among the wealthiest and most powerful institutions in human history.

Larry Page alone is worth $102 billion. Sergey Brin is worth $99 billion. Google as a company is worth roughly the entire wealth of Mexico. Telling them to distract you less is, as Hari puts it, “like telling an oil company not to drill for oil.”

But history shows that systems can change when enough people understand the game and refuse to accept it. Lead was banned. Tobacco was regulated. The attention economy can be reformed too.

It starts with recognizing that your inability to focus isn’t a personal failing. It’s the predictable result of an economic system designed to strip-mine your attention for profit. And the first step toward reclaiming it is understanding exactly who’s taking it, and why.